Location: Coppergate, Jorvík (York), England.

Date: 930-975AD (Periods 4B and 5A.)

Culture: Anglo-Scandinavian.

Estimated Social Status: Affluent urban freewoman.

This impression combines replicas of some of my favourite items found in the 10th century levels of 16-22 Coppergate. When combining them, I envisioned the daily life of someone living there and what she might wear day-to-day. As you can see, I thought there was nowhere better to photograph this impression than on Coppergate itself.

This, like all my impressions, is a continual work in progress- you can always improve and add to what you have. I’ve got household goods, personal grooming equipment and textile-working tools that would fit within this impression- they will feature in their own articles rather than making this one even longer!

That being said, I feel like this article shows several different ways the fragments and artefacts I have chosen could be pieced together to make a plausible outfit: to be dressed up or down as needed by its owner.

All photographs of me are taken by Sarah Murray. Photographs of the original finds are my own unless otherwise stated, illustrations or other images from archaeological publications are shared for educational purposes.

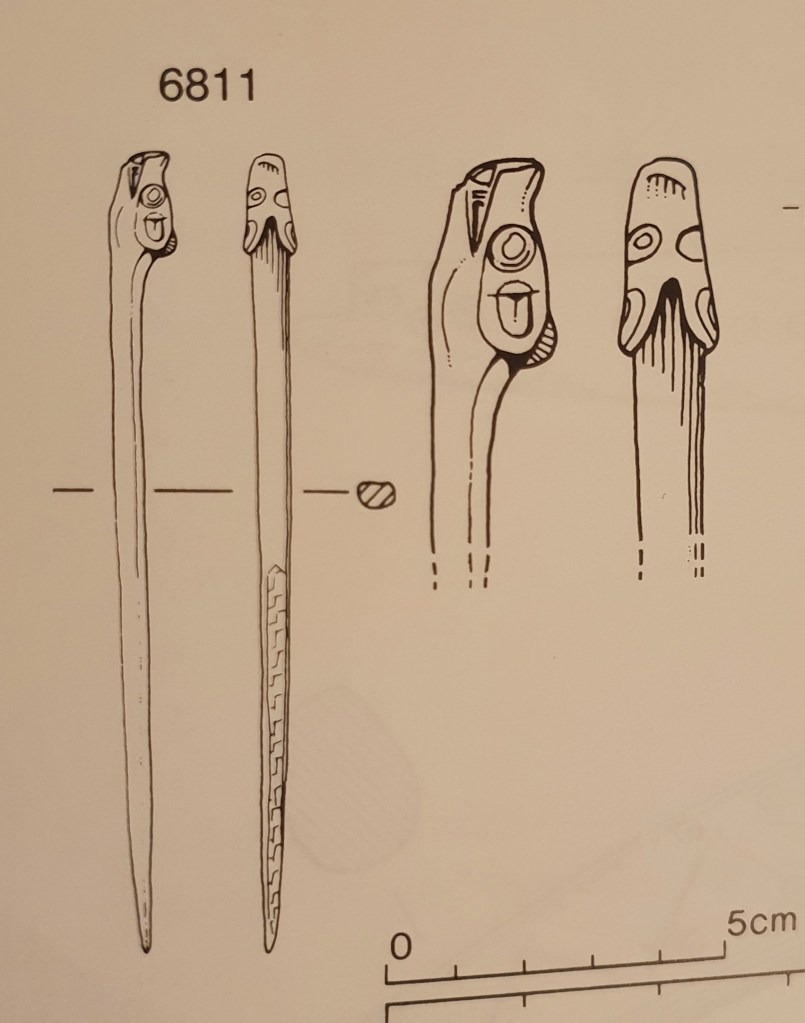

Zoomorphic bone pin. Item no. 6811, period 4B (c.930-975AD.)

This is described in MacGregor, Mainman and Rogers (1999) as being a “classic Viking Age type” of pin, with a toothy grinning beast atop it. It’s quite short at just over 11cm long and with no hole drilled through it, it would make a poor cloak pin. I chose to use mine as a hairpin and it works fairly well, though I am very precious with it. My replica is a pretty close one (albeit missing a funny little asymmetrical design on the shank) and was made for me by commission by my friend Peter Merrett.

Regarding my hairstyle, it is a really simple braid wound into a bun and secured with my pin and a fine wool braid (dyed with madder to match my dress.) I didn’t base it on anything, it is just an easy way to keep it out of my face without any modern pins or elastics. Amusingly, a friend pointed out how similar my hair looked to a disembodied bun found in the grave of a late Roman lady from York (now kept on the Yorkshire Museum, just upstairs from the Viking items!)

Wool dress in 2/2 diamond twill, dyed with madder. Inspired by fragment 1308, period 4B.

Walton (1989) describes fragment 1308 as follows:

“Tattered fragments, largest c.40x30mm, of reddish 2/2 diamond twill, (…) Dyed with madder. See also 1301.”

1301 is a “red non-reversed 2/2 twill” also dyed with madder. It was suggested that they could have been part of the same cloth originally, though I’m not sure if this implies that maybe one of the two different weaves was in fact a weaving fault. I chose to make my dress out of the diamond twill, a weave found elsewhere in the late Anglo-Scandinavian period at York (Tweddle, D. 1986)

It is interesting to note that 1301 and 1308 were also found in conjunction with another cloth, this time a mineralised grey tabby thought to be vegetable fibre, 1330. If it was indeed a vegetable fibre cloth like linen, hemp or nettle: could this represent an undershirt/dress? I usually wear a simple underkirtle made of linen tabby, but I foolishly chose not to on the hot day we took photos. This made quick costume changes a bit challenging.

In terms of pattern, I kept it very simple. I made a slim-fitting skirted dress with side gores from the waist, underarm gores for movement and a keyhole neckline. The tunics from Skjoldehamn, Moselund and Kragelund (dated to late 10th-early 11thC) all feature similar constructions with mostly rectangular bodies and triangular gores to add width and shape. English sources show ankle-length dresses fitting this silhouette on all female figures. My dress is handsewn using a mixture of madder-dyed wool thread and fine linen thread.

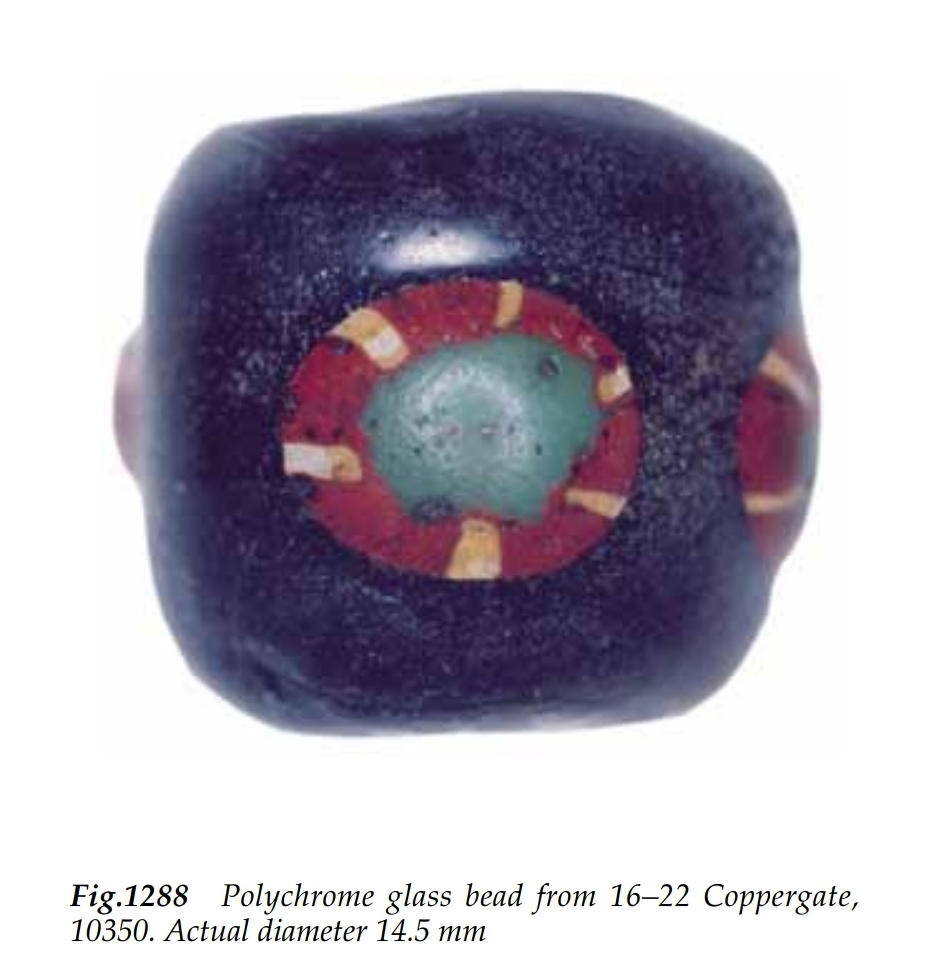

Glass bead necklace. Based on item no. 10350 and a selection of small beads found in 16-22 Coppergate, period 4B.

289 glass beads and fragments were found in Coppergate. This necklace is a creation of my own design, using a combination of beads found commonly in 16-22 Coppergate. The centre piece is a glass bead based on item no. 10350, described as a “barrel-shaped glass bead. Very dark, appearing black, decorated with green blobs surrounded by a red circle with yellow lines through” (Mainman & Rogers, 2000.) The original measured 14.5mm in diameter. My reproduction is a little more rounded than the original.

The other beads are small monochrome globular glass beads in shades of yellow, green and black. Along with blue, these are the most common colours of globular beads found in Coppergate in period 4B, with the most popular types of beads numerically being Globular (Type 2), Cylindrical (Type 3) or Segmented (Type 7.) Only 10 percent of the beads found in York were polychrome, so I wanted monochrome beads make up most of my necklace. I struggled to get appropriate segmented beads of the type I wanted, so for now I chose to make a necklace using only globular beads. These are all from Tillerman Beads and threaded on a string of linen thread.

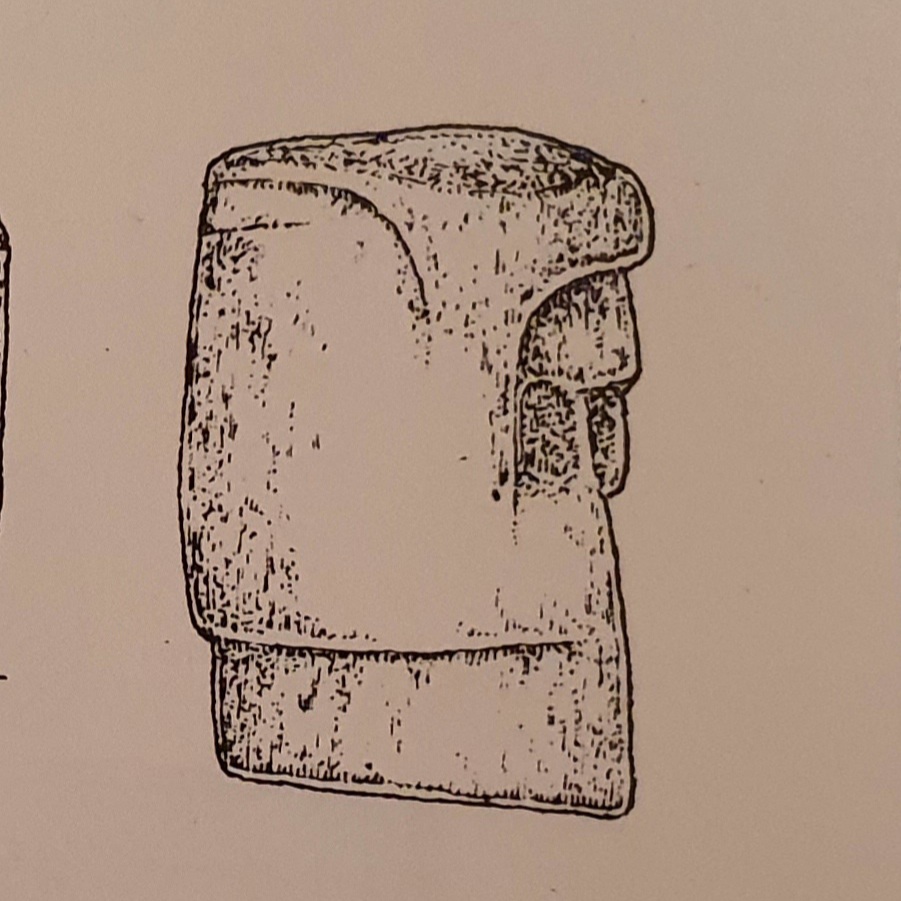

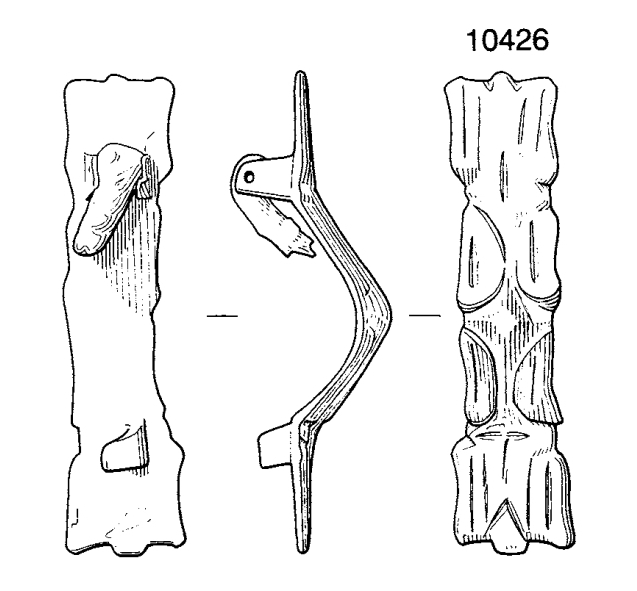

Copper alloy ansate brooch. Item no. 10426, period 4B.

Item 10426 is described as follows:

“Equal-armed bow brooch of the ‘caterpillar’ type, with a subrectangular bow with unexpanded subsquare terminals with indented edges. The catch-plate, attachment plate and part of the pin survive on the reverse. The upper faces of the terminals are decorated with incised lines, and the bow with mouldings.” (Mainman & Rogers, 2000.)

I hadn’t seen this type of brooch before and was very surprised to see it dated to the mid tenth century, as it looked alien to me. Apparently, it used to be believed that ansate brooches were most popular between the 7th and 9th centuries, but several finds in York, London and Lincolnshire indicate that they stayed in use until the 10th century.

I’m a sucker for novelty and vintage fashion, so I relished the opportunity for an alternative to the disc brooch. My replica is from Asgard.

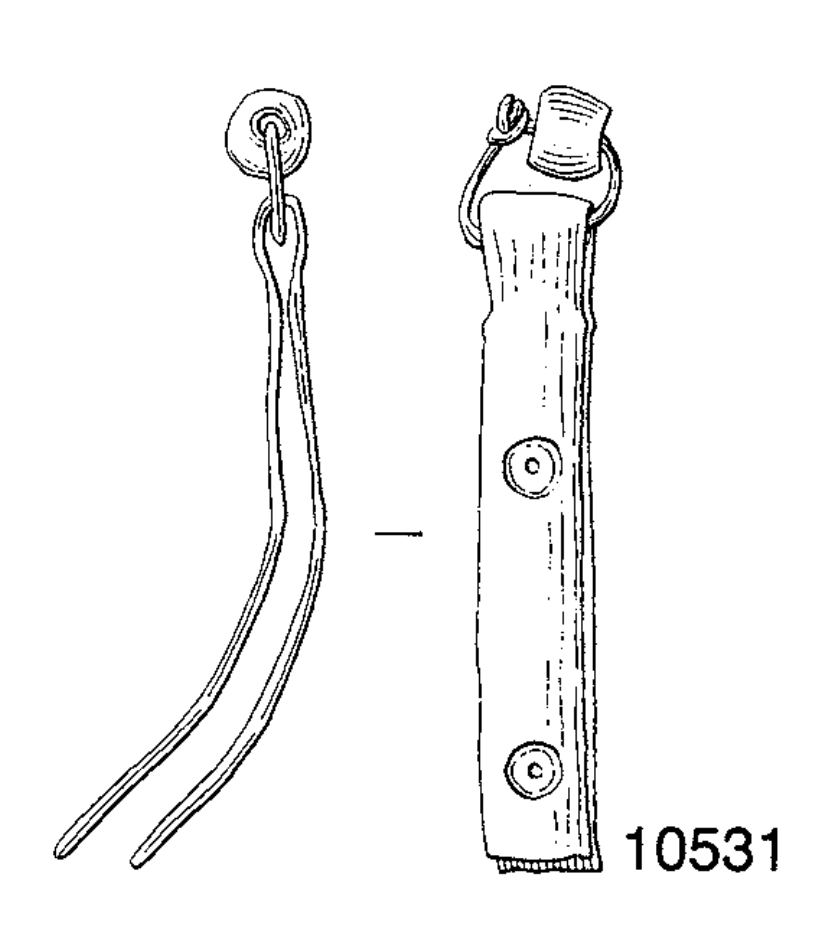

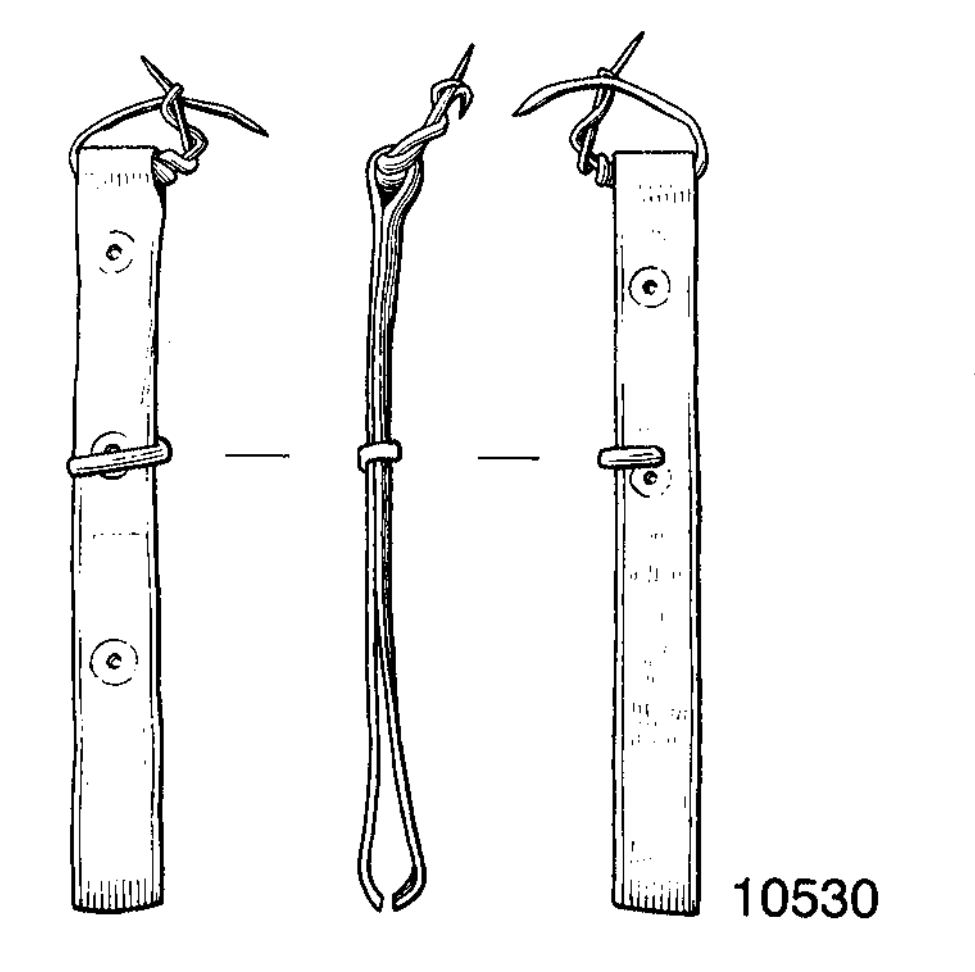

Copper alloy toiletry set with glass bead. Item no. 10531, period 5B (c.975- mid 11thC.)

This object is a bit cheeky and I will be replacing it in the future. I included it in my photo set without double-checking date and so despite kicking myself now, here it is. 10531 is a copper alloy toiletry set, with a set of little tweezers set on a twisted suspension ring.

It dates to period 5B, which is approximately 975AD to the early to mid 11th century. The lower end of this scale fits the end of my goal period, but it’s not close enough really. Thankfully, there is a similar pair found on site that dates to period 5A (the same as my silk cap) which is specifically 975AD.

You can also see a peek of what I’m up to here- with my bone needle, I’m making the York sock! It will be the subject of its own article soon, so please don’t think that I forgot the iconic naalbound sock (I could never.)

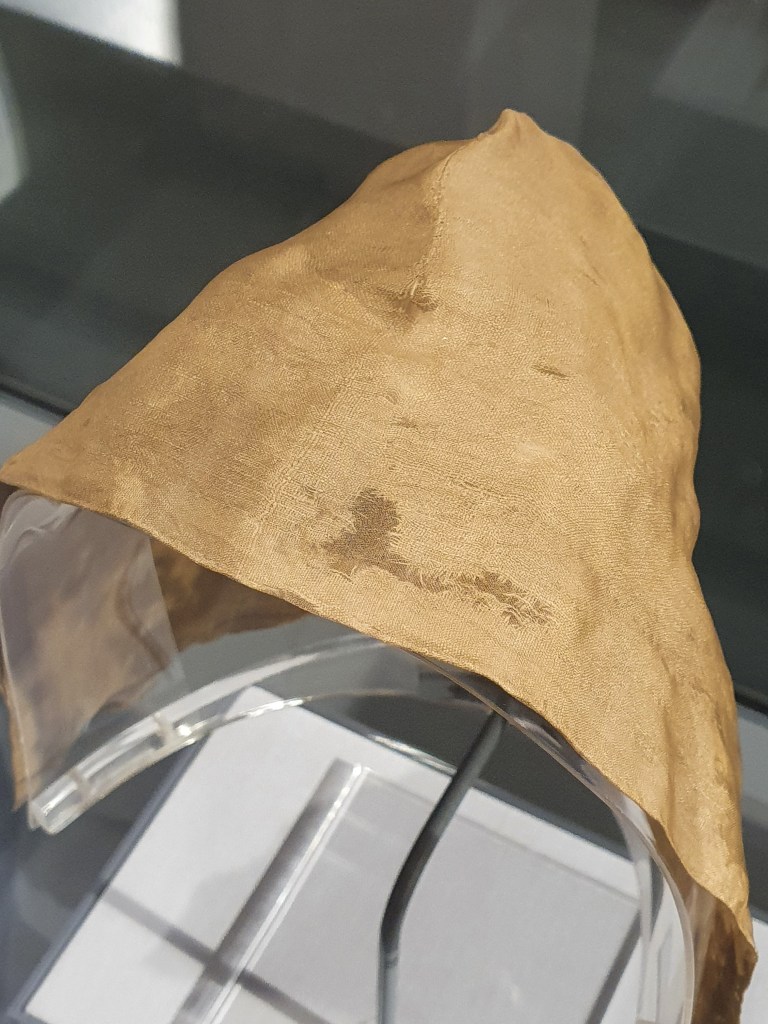

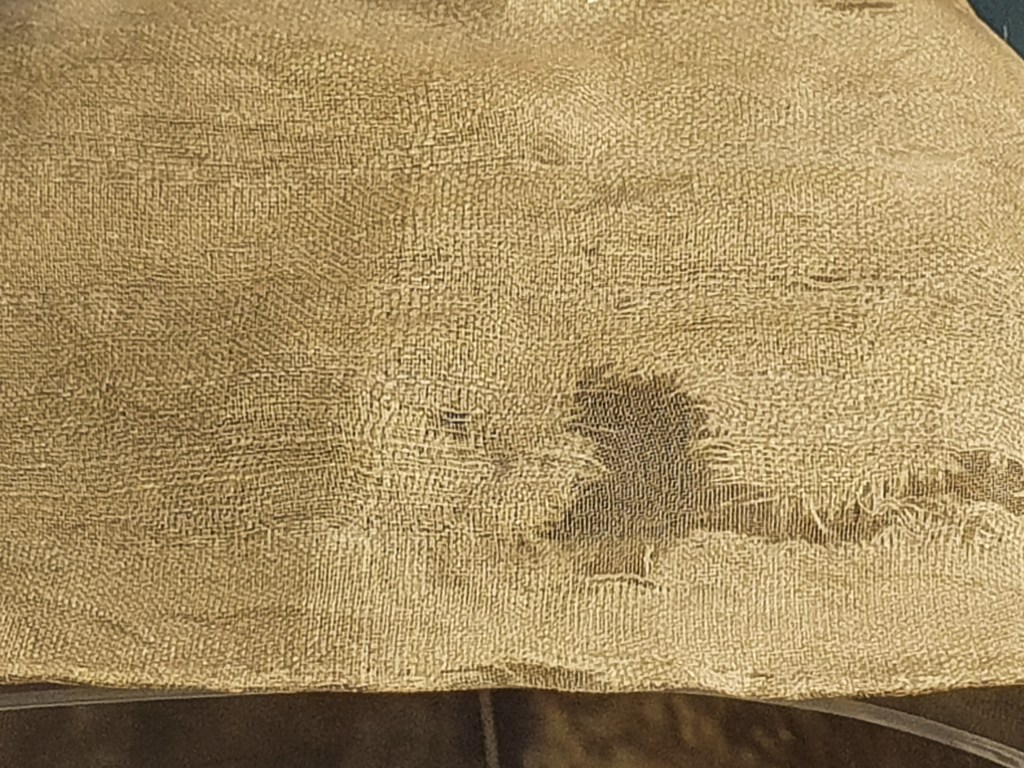

Silk cap. Item no. 1372, period 5A (c.975)

This cap is a replica of the most complete of several potential silk caps found in VA York, item no. 1372. With the exception of one fragment, they are all believed to be made of undyed silk imported from Iran. (Walton, 1989.) Of course, this would be a very expensive status symbol to own and we can imagine that the original owners would have been proud of them. Similar caps have been found in Lincoln and Dublin, with the latter providing caps made from both wool and silk. (Wincott-Heckett, 2003.)

I made my cap exactly to the measurements of the original, now kept in the Yorkshire Museum. This included placing the linen ties (not extant but indicated by stitch holes and pull marks) about halfway up the front edge of the cap- this didn’t fit me especially well.

It’s my personal opinion that this cap was originally made for an adult, with the ties being added higher up on the cap to alter it for a child’s use. Reuse of caps like this can be seen among the Dublin and York examples alike, with holes and tears being lovingly repaired to extend their use. I think with my next cap, I’ll make it to the same dimensions but attach my ties a little lower at chin level. I think I’ll alter the curve at the crown too, I made it as close as possible to the original measurements but it simply doesn’t fit my head as well as it could.

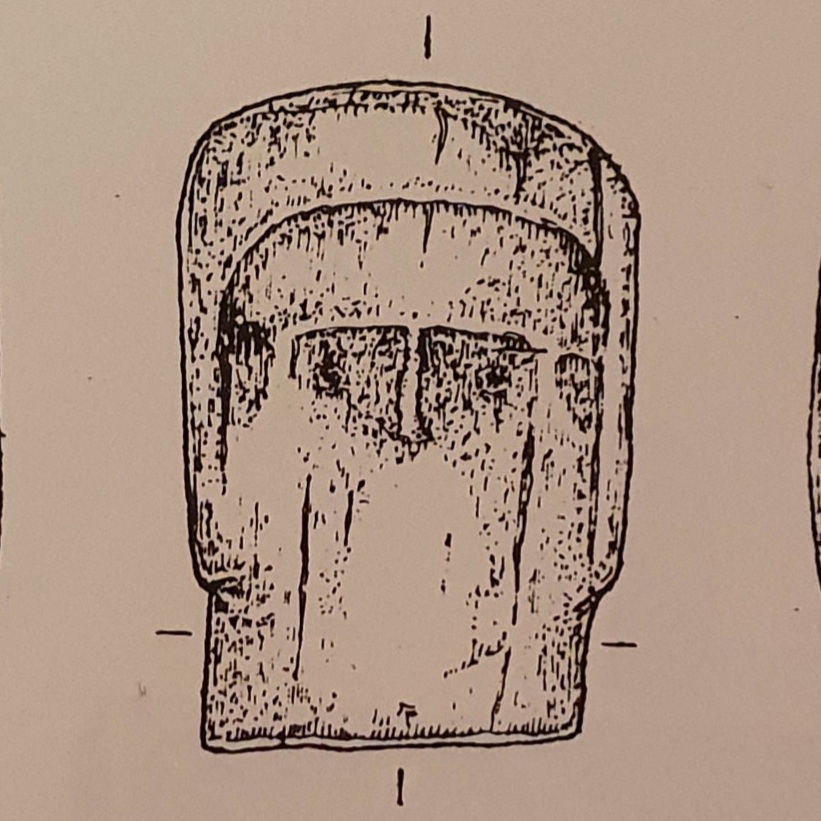

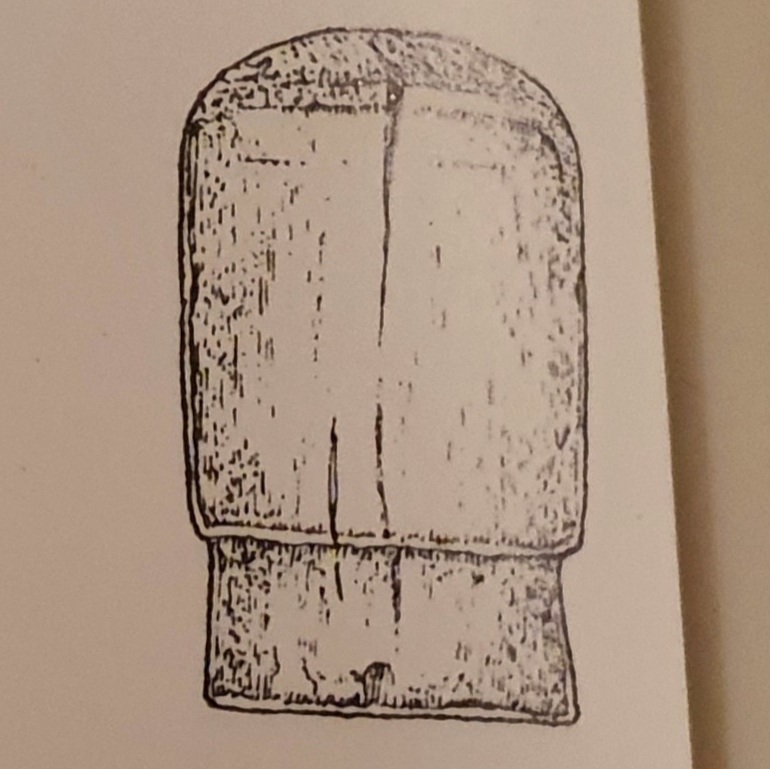

Bone weaving tablet (item no. 6679) and silk tablet woven braid (item no. 1340.) Both period 4B.

Firstly, we have a set of bone tablets based on a single example found in Tenement C, 16-22 Coppergate. It’s a very thin bone plate that is almost but not quite square: 27x24mm in dimension. My set is a little more evenly square, but that’s actually better for tablet weaving so I’m not too upset about it.

Weaving tablets from the Viking Age usually tend to be made from wood or bone, however, the average tablet is bigger than the York example at 30-40mm square. MacGregor, Mainman and Rogers (1999) suggest that the dainty nature of item 6679 means it was used for weaving fine silk braids, like the one found contemporarily on Coppergate (1340.)

I’ve already written an article on the silk and linen tablet woven band, that you can read here. In short, the original fragment was a tangled length of silk (1.47m) with a knot at one end. A few inches show evidence of having been woven with tablets, with gaps being left in the pattern that it is believed was filled with vegetable fibre, like linen.

Chemical analysis of the fibres indicated that some were dyed with madder and woad, with others only madder or no dye detected. In my recreation, I interpreted the undyed silk as being golden yellow in colour- this was based on a belief on my part that undyed silk would have been golden in period. This came from Walton’s (1989) quoting from an Old English leechbook, describing a jaundiced patient as ageolwað swa god seoluc “yellow as good silk.” If I made another version of this band, I would replace the yellow silk in the border with white or cream silk instead.

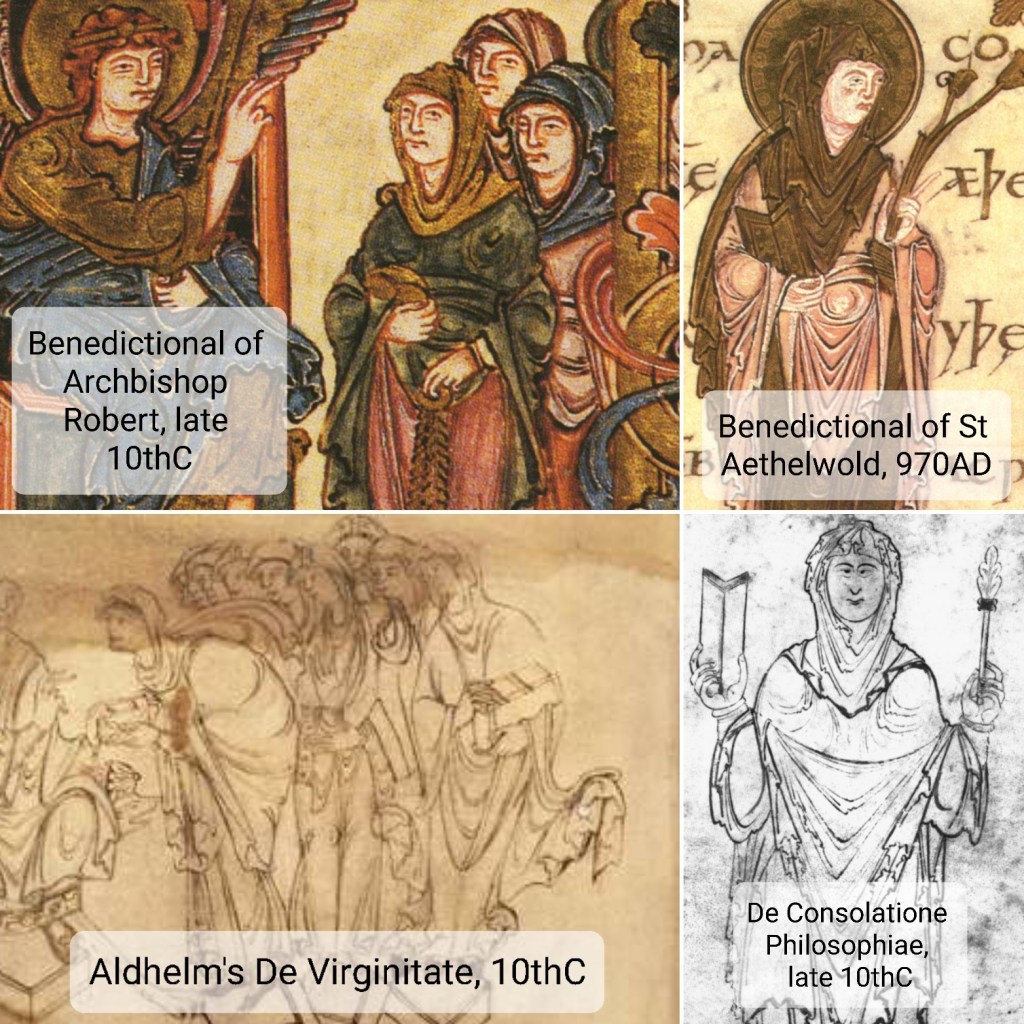

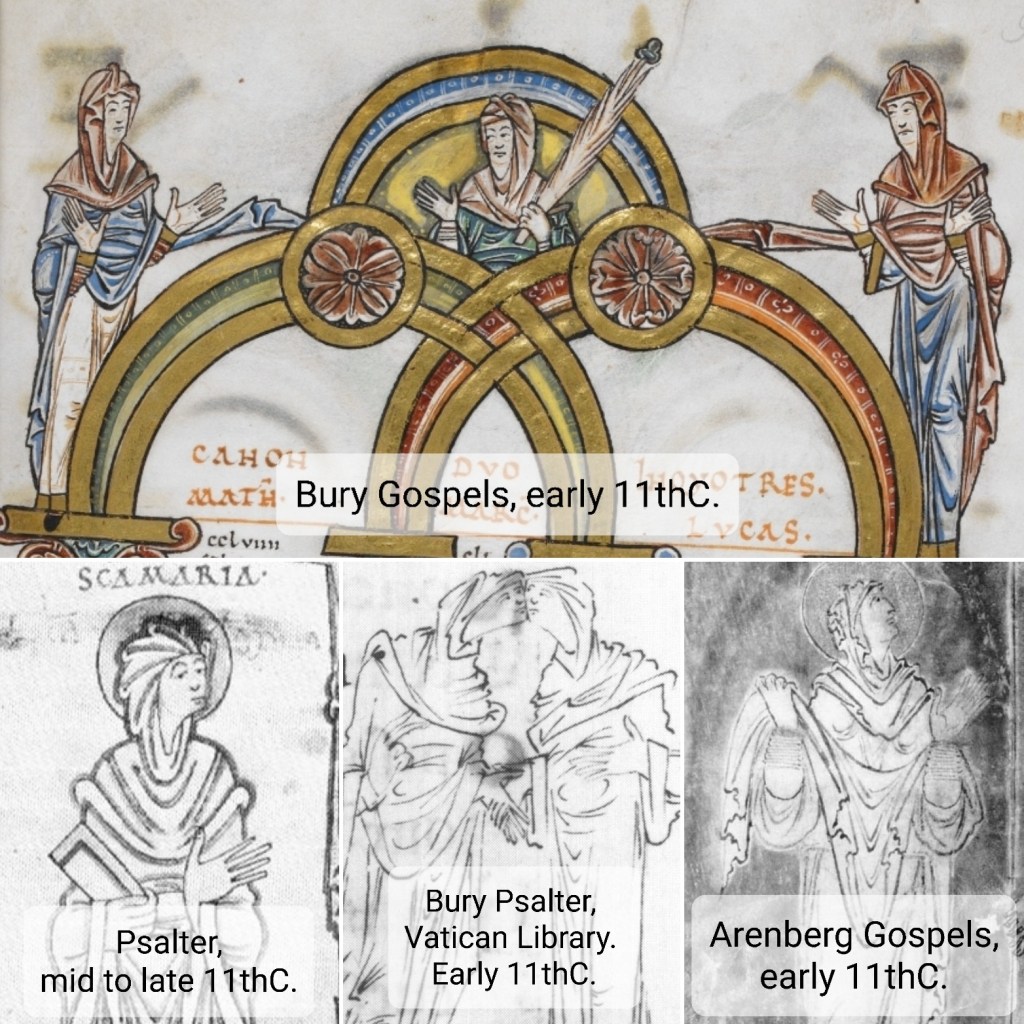

White veil in undyed 2/2 twill wool. Inspired by item no. 1300, period 4B.

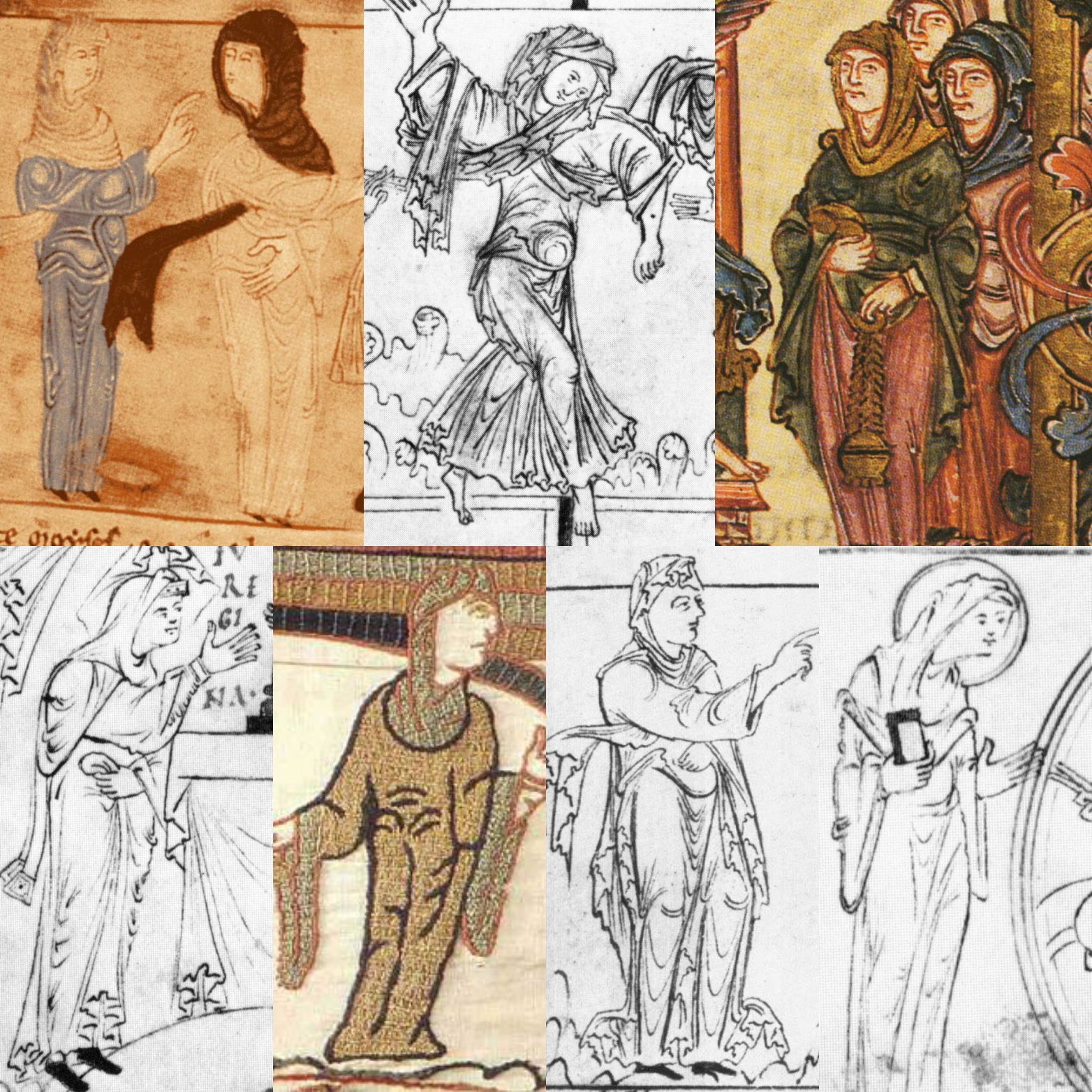

My wool veil is mostly inspired in cut by contemporary English art from the 10th century. Women are almost exclusively depicted as veiled, with the only rare exceptions being sinners in religious texts (Lot’s daughters are seen with their heads uncovered, but even they are shown veiled before they sin.)

I chose a light soft wool veil like the fabrics used in the Dublin caps and scarves (Wincott-Heckett, 2003) but unlike the Dublin examples, my scarf is a 2/2 twill, not a tabby. I aim to rectify this in the future, but for now, I feel that the length and drape of my scarf matches the period depictions and 2/2 twill is a commonly found weave in Anglo-Scandinavian York.

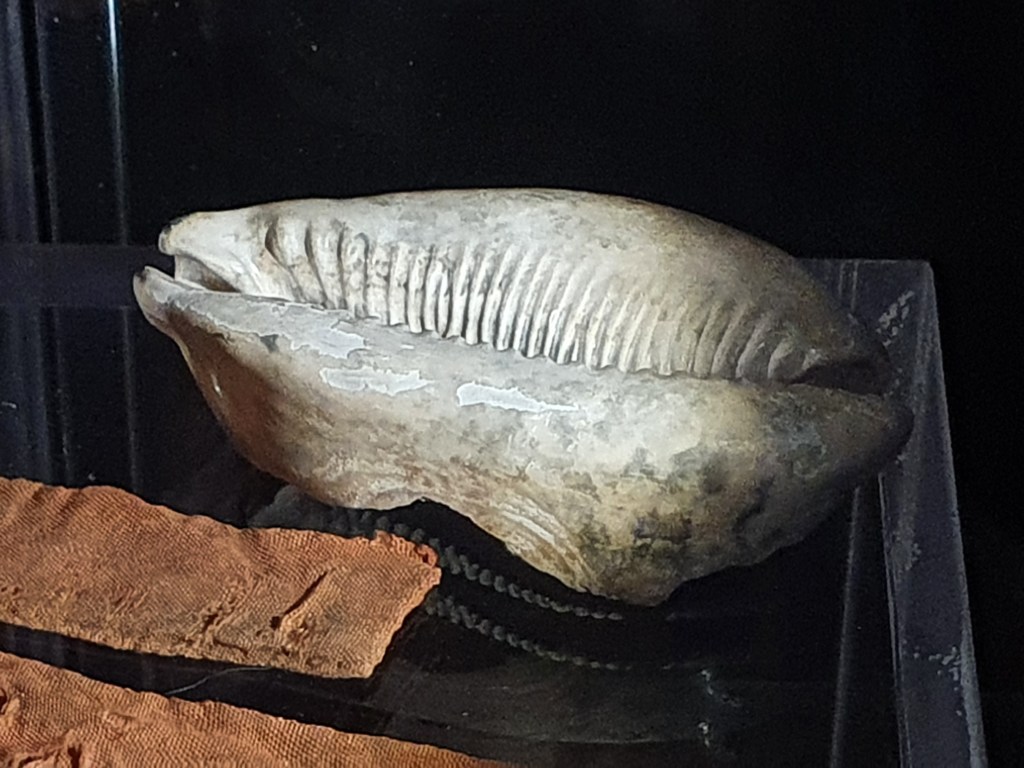

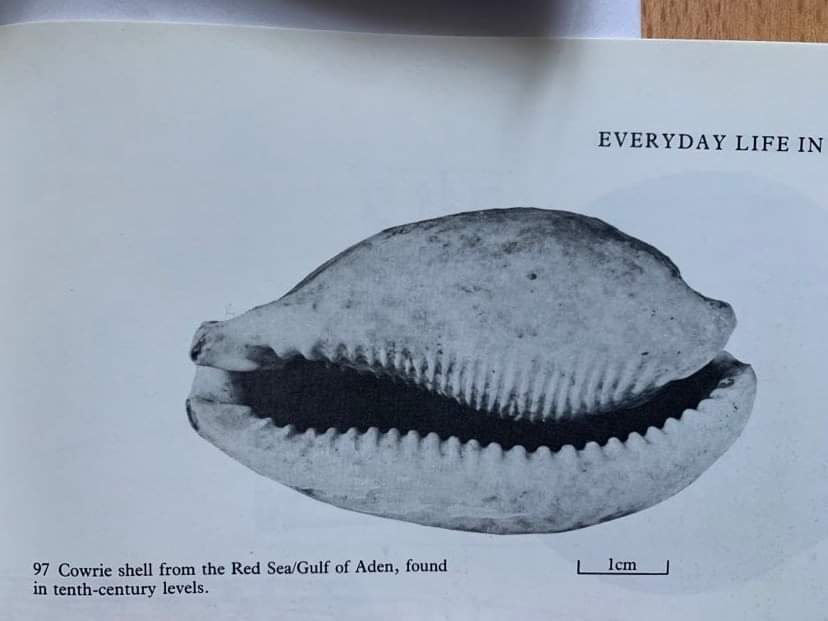

Cowrie shell Cypraea pantherina (Solander.) Item no. 11163, period 4A. (Late 9th/early 10thC- 930/5AD.)

This is a little earlier than my general timeline, but I thought it would be a fun thing to include. A panther cowrie shell found in early 10th century levels on Coppergate (11163) must have been brought by traders from abroad, as they are native to the Red Sea area. The original showed signs of saw marks, suggesting that it may have been used in the production of jewellery or ornamentation (Hall & Kenward, 2004.)

My cowrie is whole and shiny, I plan on keeping it that way. However, I am intrigued by the idea of jewellery featuring cut shell- I don’t know of any such jewellery found in York so far!

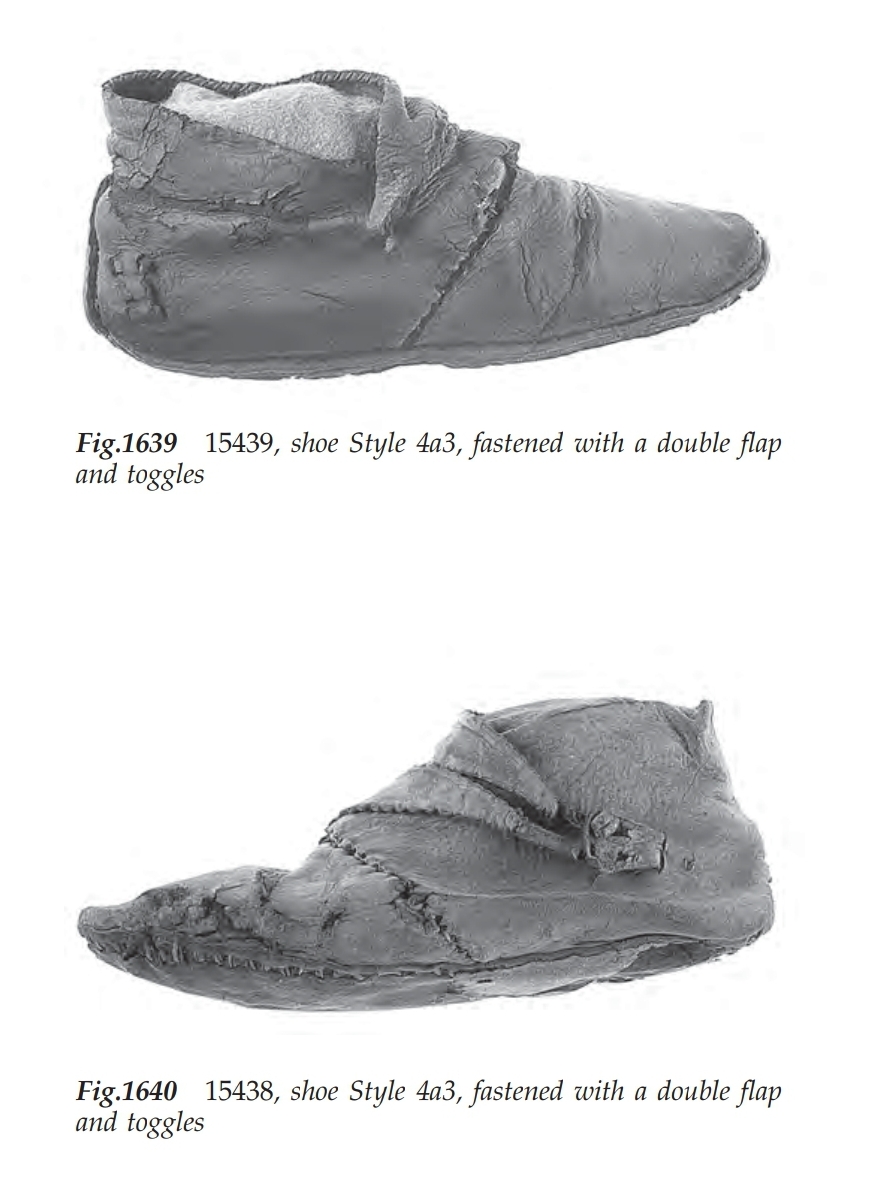

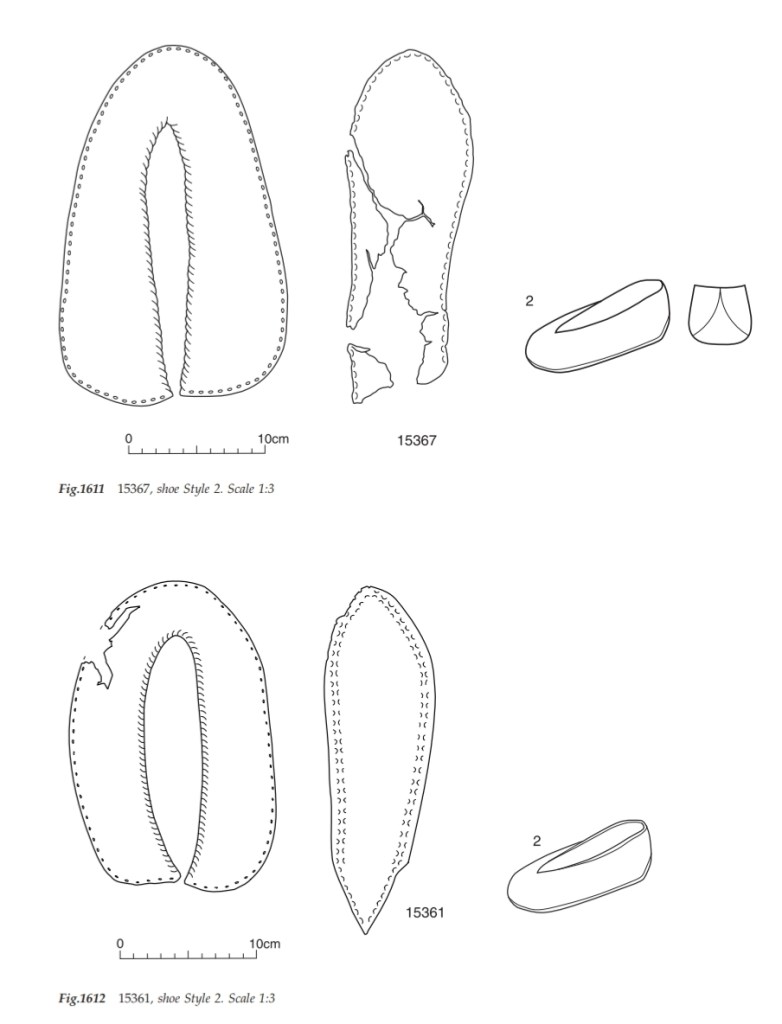

Low cut shoes. Item no. 15358, period 4B.

I was supposed to have a pair of very simple slip-on shoes made by a lovely friend, based on several pairs of shoes of Style 2. And get them I did- but they do not fit. Harrumph.

Style 2 is described as “low cut, slip on shoes with a seam at centre back” and they were found in copious amounts in York (Mould, Carlisle & Cameron, 2003.) Shoes of this style have also been found in London, Dublin and Hedeby. The York examples were constructed in a fairly standard way but variations exist, with decorative bands being added around the throat, tooling on the heel risers and the uppers being pieced using several pieces of leather.

As a style, this shoe saw popularity in York from Period 3 (mid 9thC-early 10thC) all the way until Period 5B (c.975- mid 11thC.) Interestingly, finds sharply decline to only 1 pair after the mid 11th century: coinciding with the Norman Conquest. Why didn’t the Normans like these cute shoes? We may never know. Perhaps, like me, they couldn’t get a pair to fit!

Mantle. Inspired by fragment 1308, period 4B (c.930-975AD.)

For my mantle, I used another 2/2 diamond twill wool dyed with madder, based on the same fragments that inspired my dress. While it is dyed with the same dyestuff, it is a different shade. I bought this lovely fabric from one of my favourite cloth sellers, A Selyem Turul from the Netherlands.

I drew up the pattern myself as it is quite simple, using several late English illuminations as a guide for the drape and silhouette. Towards the end of the Viking Age in England, mantles of this type replace cloaks increasingly on female figures in English art. I imagine that an affluent citydweller in a cosmopolitan place like York might seek to keep up with the fashion of the English elite by swapping her cloak for a closed garment like this.

Of course, a cloak could be just as appropriate for an impression like this- the archaeological record from the Anglo-Scandinavian period has left us a wonderful array of of cloak pins to choose from, as well as heavier textile fragments believed to belong to cloaks or overgarments.

An improvement I would incorporate for my next mantle would be to make the neckline smaller- I did not realise how much it would stretch!

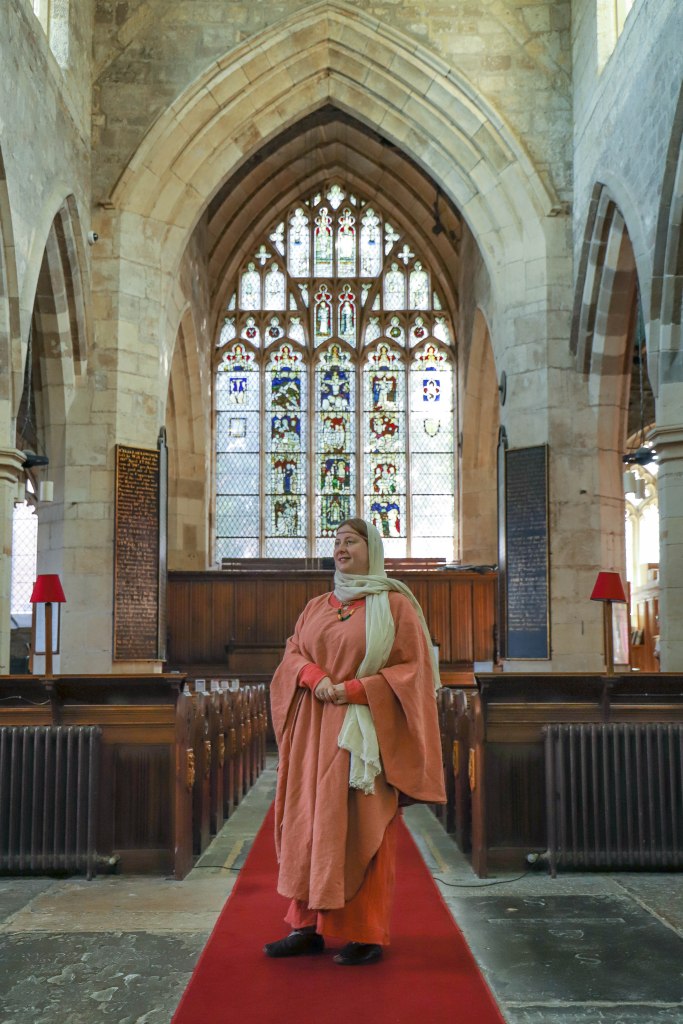

Christianity in Anglo-Scandinavian York

I wanted to represent an aspect of daily life that likely would have been as meaningful to people in the 10th century as it is to people today- faith. York was already well-stocked with churches long before the Scandinavians arrived, though only traces of these early buildings survive today.

I tried to think of my York woman’s calendar and schedule: what would she have spent her time doing? Probably much the same as me: working, doing household chores, shopping, visiting with friends and relatives. Church on a Sunday? I was raised Christian, but don’t attend services regularly. I do however find quiet time to be alone with my thoughts vital. The peaceful surrounds of old stone and silence found in historical buildings is relaxing and comforting. Did early Christians feel the same way?

I wanted to take some photographs inside a church only a stone’s throw away from Coppergate- All Saints Pavement. The current building dates to the late Medieval period, but it is believed that an earlier church and burial ground existed on the site by the 10th century. This could very likely have been my York woman’s local church.

A tiny yet beautiful grave cover was found during excavations at All Saints in the 1960s, dated to the 10th century and probably belonging to a child. Every time I see it, I take a moment to stop and spare a thought for who it belonged to and who they might have become, had they lived. Their passing must have been an enormous loss to their family, who chose to honour their little life by laying them to rest somewhere familiar with a gorgeous carved gravestone covered in sprawling interlaced beasts.

(I feel it’s very important to note that to my knowledge, there are no human remains buried underneath the 10th century grave cover. However, there are other remains buried in All Saints Pavement and it continues to be an active, consecrated place of worship. Sarah and I were quiet and respectful during the entirety of our visit.)

Religion in the Viking Age is a gargantuan topic and one I would be happy to tackle in its own article, should there be interest. I already have several projects on the go that involve churches in York- you’ll just have to watch this space.

If you liked this article, consider buying me a cup of coffee! My Ko-fi link is here: https://ko-fi.com/eoforwicproject

References

Hall, R. (1984) The Viking Dig. London: The Bodley Head Ltd.

Hall, A. & Kenward, H. (2004). Setting People in their Environment: Plant and Animal Remains from Anglo-Scandinavian York. In: Hall, R. A. (Ed). Aspects of Anglo-Scandinavian York. York: Council for British Archaeology. p.419.

MacGregor, A., Mainman, A. J. and Rogers, N. S. H. (1999) Bone, Antler, Ivory and Horn from Anglo-Scandinavian and Medieval York. London: Council for British Archaeology. pp.1948-1949.

Mainman, A. J. & Rogers, N. S. H. (2000) Craft, Industry and Everyday Life: Finds from Anglo-Scandinavian York. York: Council for British Archaeology. p2451-2671.

Tweddle, D. (1986) Finds from Parliament Street and Other Sites in the City Centre. London: Council for British Archaeology. pp.232-234.

Walton, P. (1989) Textiles, Cordage and Raw Fibre from 16–22 Coppergate. York: York Archaeological Trust. PDF.

Wincott Heckett, E. (2003) Viking Age Headcoverings from Dublin. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy.

Bibliography and other links

All Saints Pavement: https://www.allsaintspavement.co.uk/

A Selyem Turul on Facebook- the source for my natural dyed cloth (when I don’t dye it myself!) : https://m.facebook.com/DeZijdenValk

Asgard, where I got my ansate brooch replica: https://www.asgard.scot/item/ABR026-BRZ-york-equal-arms-brooch-bronze

British Library Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts: https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/welcome.htm

Kragelund tunic: http://www.forest.gen.nz/Medieval/articles/garments/Kragelund/Kragelund.html

Moselund tunic: http://www.forest.gen.nz/Medieval/articles/garments/Moselund/Moselund.html

Skjoldehamn tunic: http://www.forest.gen.nz/Medieval/articles/garments/Skjoldehamn/Skjoldehamn.html

The Roman Girl’s Hair Bun: http://www.historyofyork.org.uk/themes/roman/hair-of-a-roman-girl

Tillerman Beads: https://www.tillermanbeads.co.uk/