Today marks 958 years since the Christmas Day coronation of William, Duke of Normandy, as King of England. It has also been just over a year since the launch of an online collaborative living history project I started by the name of #AfterHastings. My colleagues and I each chose a prominent woman at the heart of the Norman Conquest and told their stories through photographs and stories shared on Instagram and Facebook. Our goal was to bring them to life for a new audience, as so many of their stories are hidden in the footnotes of history and overshadowed by the battles themselves. These women lived full and exciting lives before and after the events of 1066, yet their fates are not commonly included in mainstream treatments of the conflict.

We each learned so much from the experience and the feedback we received from our online audience was enthusiastic! The Norman Conquest still attracts a lot of interest from academics and casual history fans alike, so much so that BBC One and CBS have just released images from their own upcoming King and Conqueror series. So, to celebrate the one year anniversary of the project, I have collated all of our stories into one article for your reading pleasure. (I received full consent from each of my colleagues to do so and full credit always belongs to each of them.) Unless otherwise stated, photo credit belongs to the author of that chapter.

Even better: I have written the stories of three new women for 2024, with photos from two more excellent colleagues.

The Players

- Edith the Fair, handfast wife of Harold Godwinson: @historywithjess

- Edith of Wessex, Queen of England, wife of Edward the Confessor, sister of Harold and Tostig Godwinson: @aelettethesaxon

- Judith of Flanders, Countess of Northumbria, wife of Tostig Godwinson: @einnstjarna_weaving

- Gytha of Wessex, younger daughter of Harold Godwinson and Edith the Fair: @eoforwicproject

- Gunnhild of Wessex (the Younger), younger daughter of Harold Godwinson and Edith the Fair: @skadi.blodauga

- Elisiv of Kyiv, Queen of Norway, wife of Harald Hardrada: @hikikomorikikimora

- Tora Torbergsdatter, second wife of Harald Hardrada: @northseavolva

- Matilda of Flanders, Queen of England, wife of William the Conqueror: @rowena_cottage_costuming

- (NEW FOR 2024!) Gytha Thorkelsdōttir, Countess of Wessex, mother of Harold, Tostig, Queen Edith, Gunnhild (the Elder), wife to Godwin: @paulaloftingwilcox

- (NEW FOR 2024!) Edith of Mercia, second wife of Harold Godwinson, former Queen of Wales: @daisydrawsbad

- (NEW FOR 2024!) Gunnhild (the Elder), daughter of Gytha Thorkelsdōttir and Godwin, sister of Harold, Tostig and Queen Edith (and others): @eoforwicproject (again!)

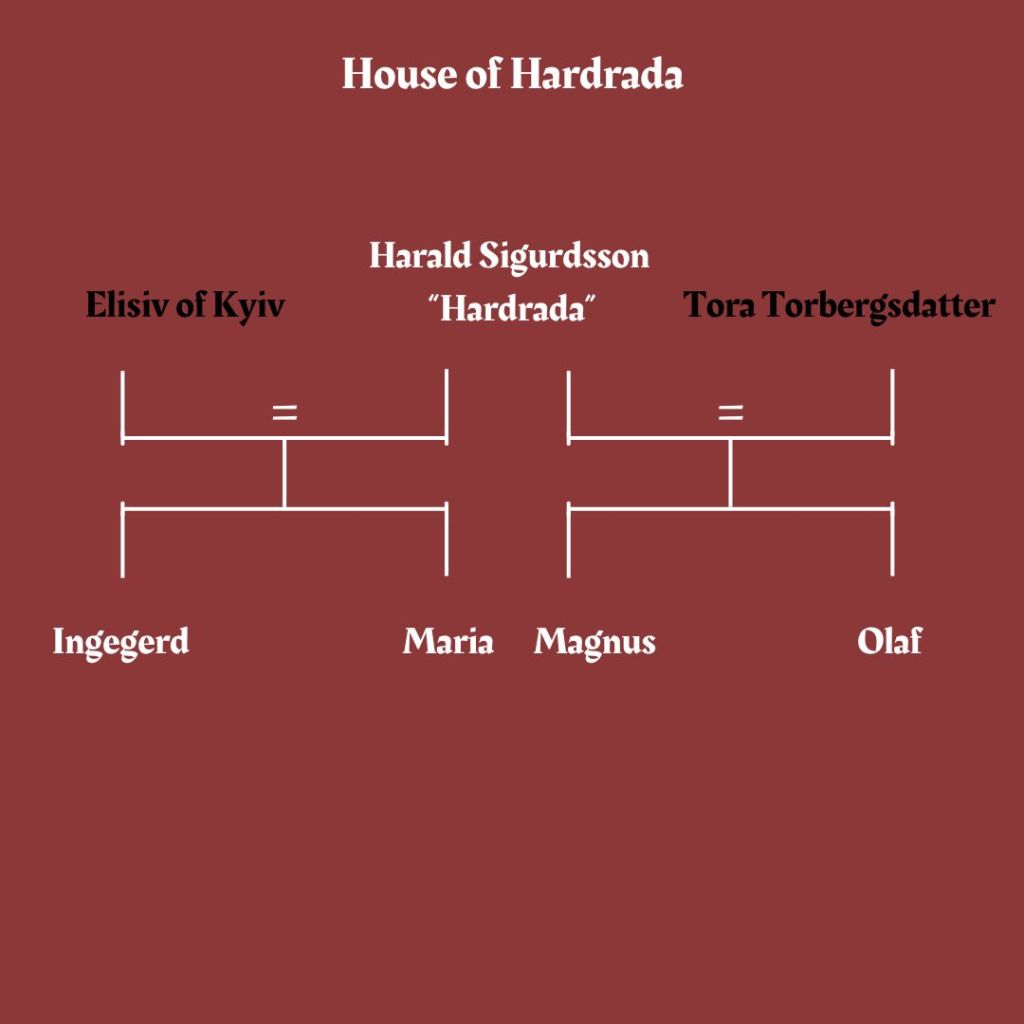

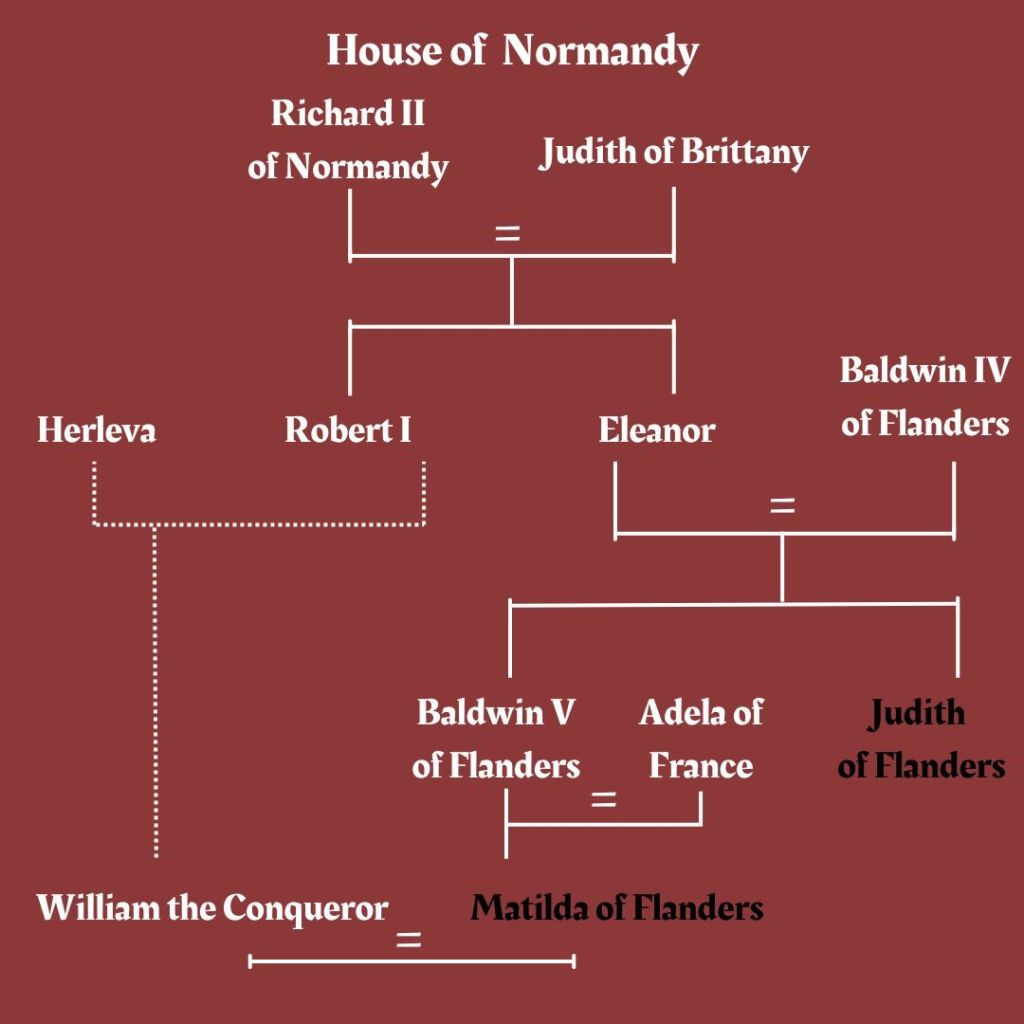

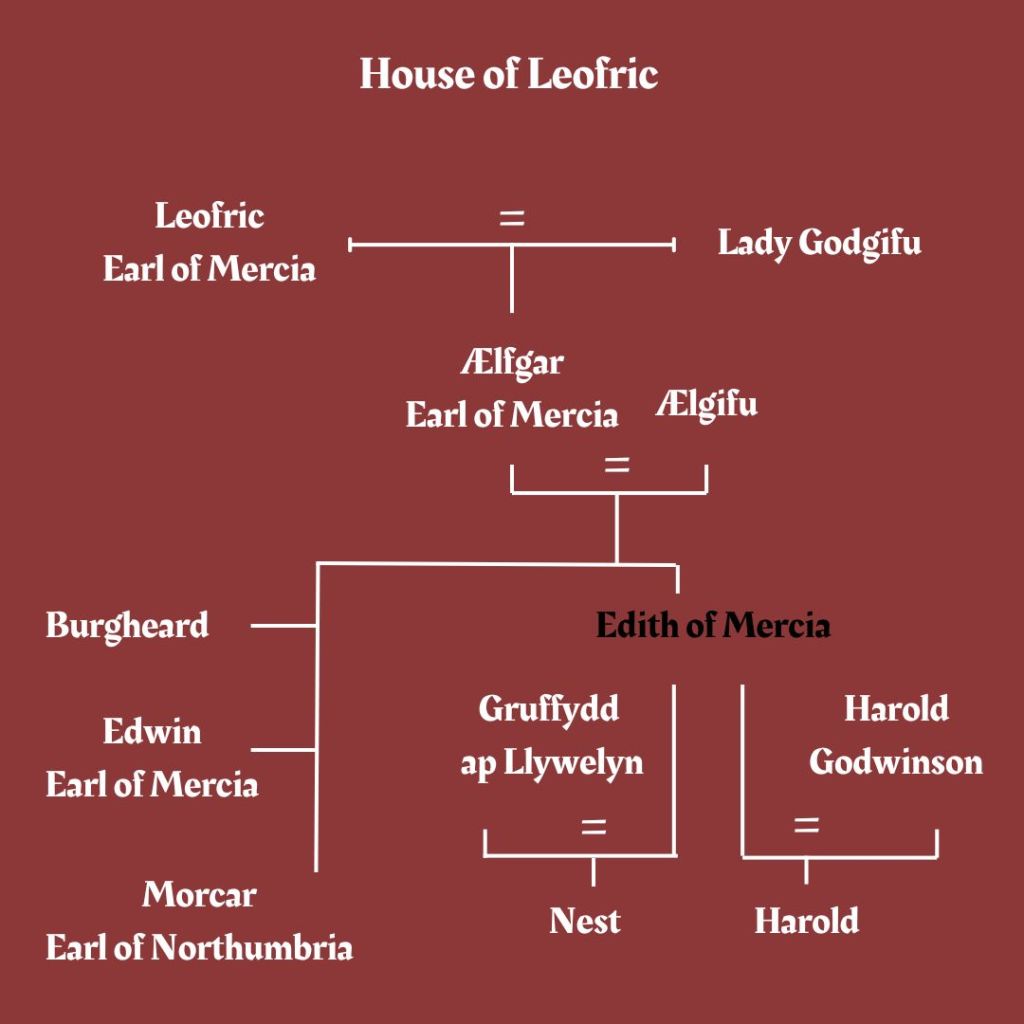

Family Trees

Reading Medieval history can be pretty complicated, even more so when everyone seems to have the same damn names. I’ve created these handy family trees to help you visualise the social and familial bonds and keep track of who is who. The names in black are women who are featured in the #AfterHastings project- you get an extra shiny gold star from me if you can find the ladies who pop up in more than one of the family trees.

Another housekeeping note before we begin: my colleagues and I have generally used modern spellings of peoples’ names for ease and have added sobriquets and bynames where necessary. We are very much aware that our Ediths would have more likely answered to Eadgyth (or Eadgifu or Aldgyth or whatever you like,) but spelling was not standardised in the 11th century. Therefore, to limit confusion and answer the prayers of our dyslexic friends, we have mostly stuck to modern English spellings.

Edith the Fair, handfast wife of Harold Godwinson: @historywithjess

“Swan-necked, men named her… her neck of smoothest pearl…”

Edith Swanneck (Old English: Swanneshals) left an extraordinary impression on her contemporaries as a woman of virtue. As wife to the last Anglo Saxon King, her story is inextricably linked to that catastrophic October day in 1066, and her involvement is often peripheral to the main event. Yet Edith’s life, when considered closer, is a story of true love, devotion, loss and strength in adversity.

But who was the real Edith?

She is known to posterity by many names given in her own lifetime. Her English name was Eadgyth, but she is also known variably as Eadgifu and Eadygo. The Doomsday Book later latinises her name to ‘Eddeva’, yet all variations come with the same caveat; “pulchra” or “fair”. Edith was well known as a strikingly beautiful, gentle young woman and an incredibly wealthy one at that.

Born around 1022 to Lady Wulfgyth and the warrior Thorkell the Tall, Eadgyth Thorkellsdottir, as she would have been known prior to marriage, was half English and half Danish. She was also of royal blood; her mother, Wulfgyth, was a daughter of Aethelred the Unready. Her father’s close connection with King Cnut alongside her own royal blood meant Edith spent a great deal of time at the English Court and she would go on to own vast lands and properties bestowed upon her parents in East Anglia .

Edith’s marriage to Harold in around 1045 would have brought prestige, power and influence to the Godwinson name. Both attractive and in their early 20s, it is generally agreed that the two fell very much in love. Their handfasted ‘more danico’ wedding was customary and legitimate to the Anglo-Danish society they lived in and marked the beginning of a 21-year devoted and loving marriage.

Harold’s ‘concubine’. This was how the Normans, in the aftermath of the Conquest, referred to Eadgifu Swannashals (Edith Swanneck). To diminish the legitimacy, loyalty and truth of her relationship with Harold was part of a broader attempt to bring shame and ruin upon Harold’s claim and legacy, thereby legitimising the invader’s claim to the throne.

As is so often the case with history, her story has long been one known only through the lens of the victors.

The term ‘concubine’ implies Eadgifu was a weak, powerless, inconsequential woman. But that presumption, my good friends, could not be any further from the truth. She was very much an equal to Harold by the time of their marriage, as an experienced estate and household manager, and was in no short supply of intelligence.

Second only in wealth to the Queen of England (!) in 1065, the Domesday book shows us that Eadgifu owned 27,000 acres of land, at least 135 manors and several town houses across East Anglia and beyond. It is likely, even, that her properties included several water mills, an advanced technology that was changing Anglo-Saxon society for good.

Eadgifu would have spent much time travelling between her favourite manors and landholdings, collecting rents, entertaining guests, and childbearing. From the Domesday book, it is clear that Eadgifu’s lands were a reliable source of income before, during and after the conquest.

And amidst the somewhat dull entries of the Domesday records is a small spotlight on Eadgifu’s personality; an entry in which she supports, enforces and presumably maintains the claim of a woman to retain her lands in a dispute with her estranged husband.

Far from weak then, Eadgifu was influential, powerful, and compassionate. With her royal connections and political awareness, she would have made quite the impression on Anglo Saxon England. For a woman of such importance, it is hard to accept that her life and actions during the tumultuous final decades of Saxon England are so often boiled down to one word: concubine. Perhaps this project can change that.

“And Harold the King, he loved the comely girl”

As the young and beautiful Eadgifu grew into an influential and admired woman of 11th century England, so too bloomed her love and loyalty to a man who by all accounts appears to have been a dutiful, loving husband & father, as well as a commanding and trusted noble.

Eadgifu and Harold Godwinson’s marriage marked the beginning of an enduring love that faced joy and heartbreak. Both hailing from half-Danish backgrounds, Harold’s ties to Danish royalty intertwined seamlessly with Edith’s connections to English royalty, creating a union that was not only profound but visually striking.

The impact of Eadgifu’s presence in Harold’s world cannot be understated; she played a pivotal role in shaping Harold’s destiny and his meteoric rise to the throne. Together, they wove a narrative of power and prestige.

Their commitment to their family resulted in remarkable harmony between them and their children, a peaceful existence that is quite rare amidst the throng of medieval aristocratic families so often marred with controversy and betrayal.

Their unwavering love is captured in a small snippet from ‘The Life of St Dunstan’ that mentions the poignant burial of their stillborn son at Canterbury Cathedral. In around 1048, the couple experienced the profound grief of a stillborn child. Unbaptised, the baby could not be buried on consecrated ground. Yet, Eadgifu and Harold went to great and extraordinary lengths to have their baby buried in the hallowed grounds of Canterbury Cathedral, near St Dunstan’s shrine. This act of devotion speaks volumes about their commitment to each other, their family and their faith. They would go on to have 6 children in total.

Eadgifu and Harold navigated the intricacies of medieval society together for 21 years. On the eve of that fateful day in 1066, it is easy to imagine Harold taking comfort in Eadgifu’s calm and loving company one final time.

“Discovered hath Edith the corpse of the king. No longer need she seek; No word she spake, she wept no tear, She kissed the pale, pale cheek.”

As the infamous Battle of Hastings loomed, one theory places Edith Swanneck and her young son Ulf in Harold’s manor in nearby Crowhurst. It is interesting that Edith should be close by at all; she was Harold’s wife, but she was not his Queen. Harold had married Aldgytha of Mercia (another Edith) shortly after his coronation.

It is generally accepted that this marriage was purely political. But how would Edith have felt? Would she have seen it as a betrayal? Would she have agreed it was a necessary move to secure Harold’s new position?

There is no evidence to suggest that Edith or their 6 children were disregarded after the marriage, but as the handfasted wife of the now legitimately married King, Edith would not have been welcome at court.

So, had Edith been spending time with Harold privately prior to Hastings at Crowhurst, away from the punitive gaze of his new Queen?

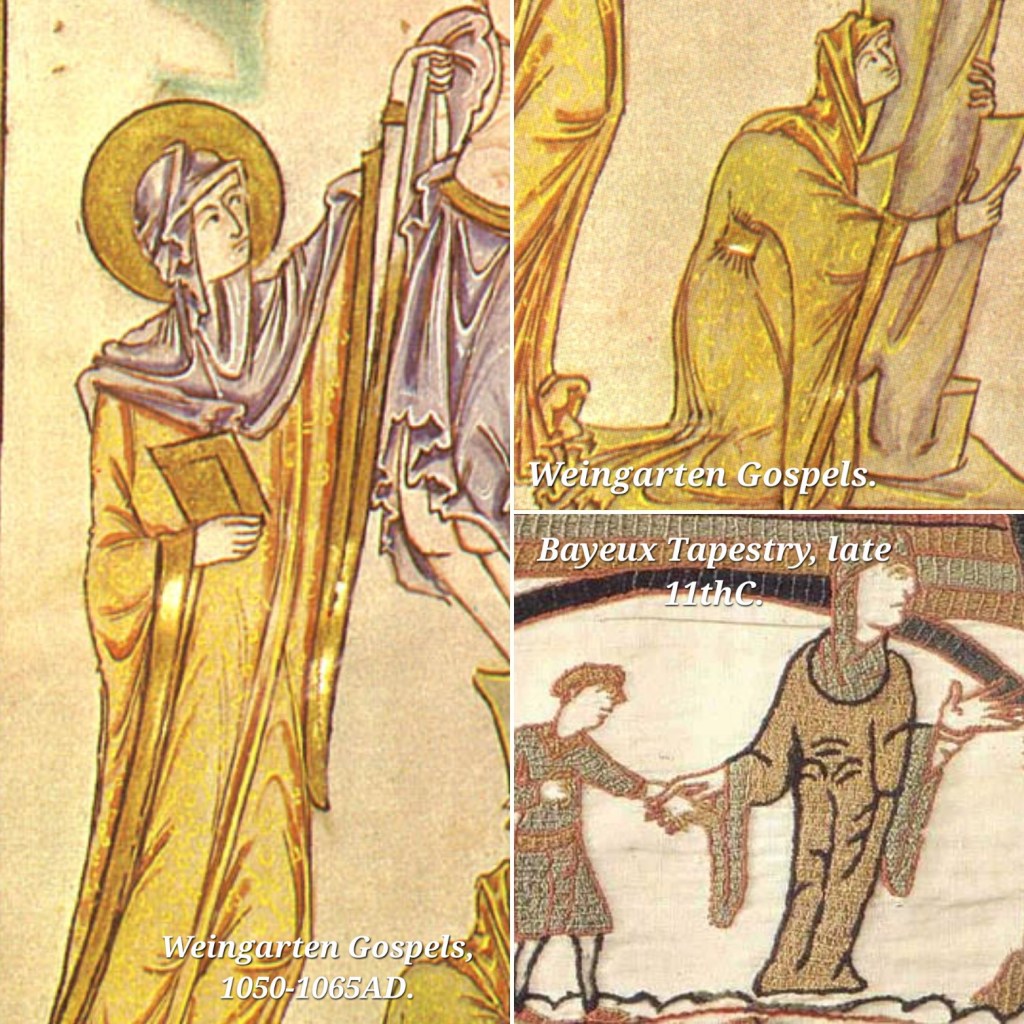

It was arguably at Crowhurst that Edith was captured by William’s men. A certain scene on the Bayeux Tapestry is tempting evidence; a noblewoman is seen escaping from a burning manor house with her son during William’s invasion. If true, it would provide some explanation for the speed with which William was able to present Edith in the aftermath of Hastings, forced to perform the heartbreaking act of identifying Harold’s mutilated body.

The Waltham Chronicle recounts this tragic story. Edith, captured by William’s men, is forced to trawl through the carnage of the battlefield to find Harold. She does this with great strength, locating her husband’s body, but is cruely denied the mercy of burying him.

In the space of less than a year, Edith’s world is turned upside down. The catastrophe of invasion was almost total: not only had she lost her husband and King, but her country was now in foreign hands, and her ancestral lands were stripped, leaving her with nothing. How could she pick up the pieces of her new, shattered reality?

The Final Chapter.

After the Battle of Hastings, Edith Swanneck vanishes from historical records, sparking speculation about her fate. It’s unclear if she was a hostage of William, potentially due to her status and wealth. The ambiguity surrounding her captivity raises questions about strategic use; if he perceived her influence as a threat, William might have kept her close by to control her sons’ rebellious activities. The silence on Edith contrasts with her son Ulf’s documented hostage status in Normandy.

Edith’s fate may have eventually shifted, especially after her sister-in-law, Edith of Wessex, gave William the treasury. This act raises suspicions of treachery – Edith of Wessex appeared to flourish post conquest whilst her family was destroyed – or was a possible deal reached, including Edith Swanneck’s freedom?

If freed, it is possible that Edith would join Gytha, her mother-in-law, in Exeter, which would place her at the epicentre of the 1068 resistence against William. Was she subsequently one of the widows that joined Gytha on her final escape and crossing to Flanders ? Did she then journey to Denmark, where she had familial connections to royalty? It would make sense to seek out family abroad – England was no longer safe.

If in Denmark was she involved in the spectacular marriage arrangement for her daughter, another Gytha, to a Prince of the Kyivan Rus’? She was a resourceful, intelligent woman and more than capable of arranging such an advantageous marriage.

Without concrete evidence, Edith Swanneck’s fate remains a mystery, leaving much to be desired in historical records. Whether in Denmark or another refuge, one hopes Edith, a woman of fortitude, found some peace in the final chapter of her life.

Edith of Wessex, Queen of England, wife of Edward the Confessor, sister of Harold and Tostig Godwinson: @aelettethesaxon

The whole text can be viewed online here: https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-EE-00003-00059/28

Part 1: Edith Godwinsdottir was born in around 1025.

Her father Godwine was one of the most powerful English Earls under King Canute. Her mother Gytha was the daughter of Danish chieftain Thorkel Sprakling. Edith was therefore both Saxon and Dane and came from nobility on both sides.

She also had nine siblings, the most famous being Harold Godwinson.

Edith was a very intelligent, pious and polite woman, educated in languages, embroidery and weaving as well as maths and astronomy at Wilton Abbey.

Of course, as a woman of high status, she became a pawn in the royal game of chess. But luckily for our Edith, she knew how to play. Her father, Godwine supported Edward the Confessors claim to the throne and wanted him to marry Edith. Despite Edward not liking Godwine for his involvement in his brothers murder, Edward agreed because he needed Godwines military support.

The couple were married on 23rd January 1045, when she was about 20 years old and Edward was 40. Edith was now the Queen of England.

As far as we know, Queen Edith was the only Saxon queen of the 11th Century to be crowned. Her coronation was held in Winchester.

Edith was a trusted advisor to Edward and had him dressed in finery, with their apartments regally decorated. However, when Edith’s father Godwine was banished in 1051 for misconduct, Edith was sent to a nunnery and her lands were taken. They had no children and he wanted a divorce. A year later though, Godwine was back, Edith and Edward were back together and Edith became one of his closest advisors. Edith increased her loyalty for her father and brothers and she was getting more and more powerful.

My impression is inspired by this image of her coronation.

Part 2: Edith and Edward had no children. Whether this was because Edward kept a vow of celibacy, or because he didn’t want to give her family the satisfaction of having a royal heir, the reason remains a mystery. Yet, between 1051-52 whilst the Godwin family were exiled, William of Normandy came to visit Edward. It was during this visit that Edward supposedly named William as his successor.

In 1053, Edith’s father Godwine dies. Her brother, Harold Godwinson steps into his place as Earl of Wessex. Now the second most powerful man in the country, he dealt with rebellions in Wales and northern England. As a result, Edward named Harold as his successor too.

In 1057 when their father dies, Edith adopted Edward’s nephew’s son Edgar and daughter Margaret as her own, placing Margaret in her beloved Wilton Abbey to be educated as she herself was.

These photos were taken at Escomb Church, County Durham at one of the few Saxon churches remaining in the country. It is a 7th Century church, so would have been old even when Edith was around, but whether she ever visited this church we will never know.

Part 3: Edith also supported her other brother Tostig as Earl of Northumbria. He was extremely unpopular, coming down hard on anyone who opposed him. Edith, as his right hand woman, was accused of engineering the murder of Gospatric, the Northumbrian lord in 1064.

In 1065, Tostig was away hunting with King Edward, his brother-in-law when Morcar was elected as Earl of Northumbria. Who was sent to deal with this? None other than Edith and Tostig’s brother Harold Godwinson. However, Harold agrees Morcar should be Earl, despite his siblings’ protests. Tostig was exiled as a result.

In 1065 after building Westminster Abbey for 23 years, King Edward was too ill to attend its dedication. Queen Edith attends in his honour. Eight days later King Edward the Confessor dies. The very next day, her brother Harold Godwinson is named the new King of England.

Her husband, the king, was dead. The new king, her brother Harold, had gone against her. Her beloved brother Tostig was exiled.

Things weren’t looking too good for Edith.

Part 4: Edith lost her beloved brother Tostig at the Battle of Stamford bridge, when her other brother King Harold marched up to fight against him and the King of Norway, Harald Hardrada. Tostig had joined forces with Harald after being exiled and was furious with his brother.

William of Normandy arrived soon after, and on the 14th October 1066, at the Battle of Hastings, Edith lost three more brothers. Gyrth, Leofwine and King Harold Godwinson died leaving William the Conqueror as the new King of England.

William requested that Edith pay tribute to him, which she did and so retained her wealth and lands. William greatly respected Edith, despite her connections with the man he’d just waged war with. She was the only one of the English royals who thrived after the Norman Conquest. In the Domesday Book she is recorded as the richest woman in England.

She also commissioned a book called ‘Vita Ædwardi Regis’ about her husband King Edward. It is also argued that Edith organised for the Bayeux Tapestry to be made. She is one of only three women to be featured on there.

Part 5:

The nobility of your forbears magnified you, O Edith,

And you, a king’s bride, magnify your forbears.

Much beauty and much wisdom were yours

And also probity together with sobriety.

You teach the stars, measuring, arithmetic, the art of the lyre,

The ways of learning and grammar.

An understanding of rhetoric allowed you to pour out speeches,

And moral rectitude informs your tongue.

The sun burned for two days in Capricorn

When you discarded the weight of your flesh and went away.

These are the words written by the prior of Winchester Cathedral, Godfrey of Cambrai, upon Edith’s death on December 18th 1075 in Winchester, aged 50. She was buried next to her husband King Edward the Confessor at Westminster Abbey. King William I arranged her funeral.

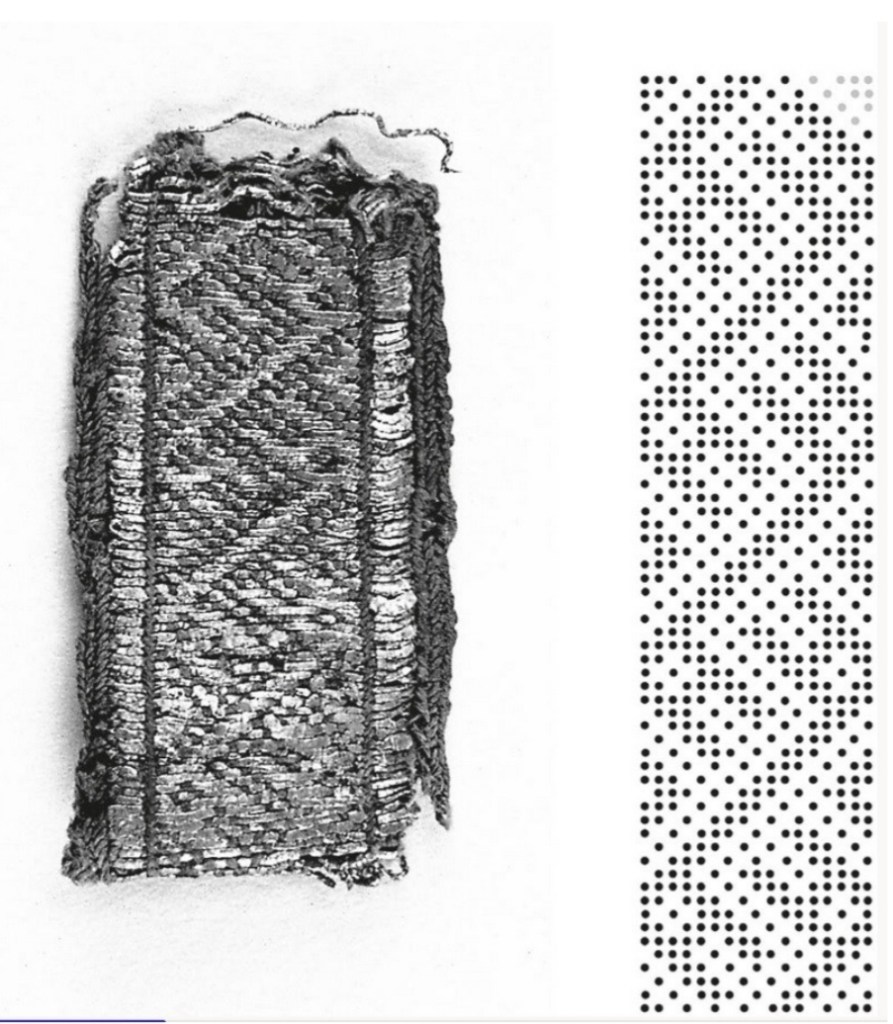

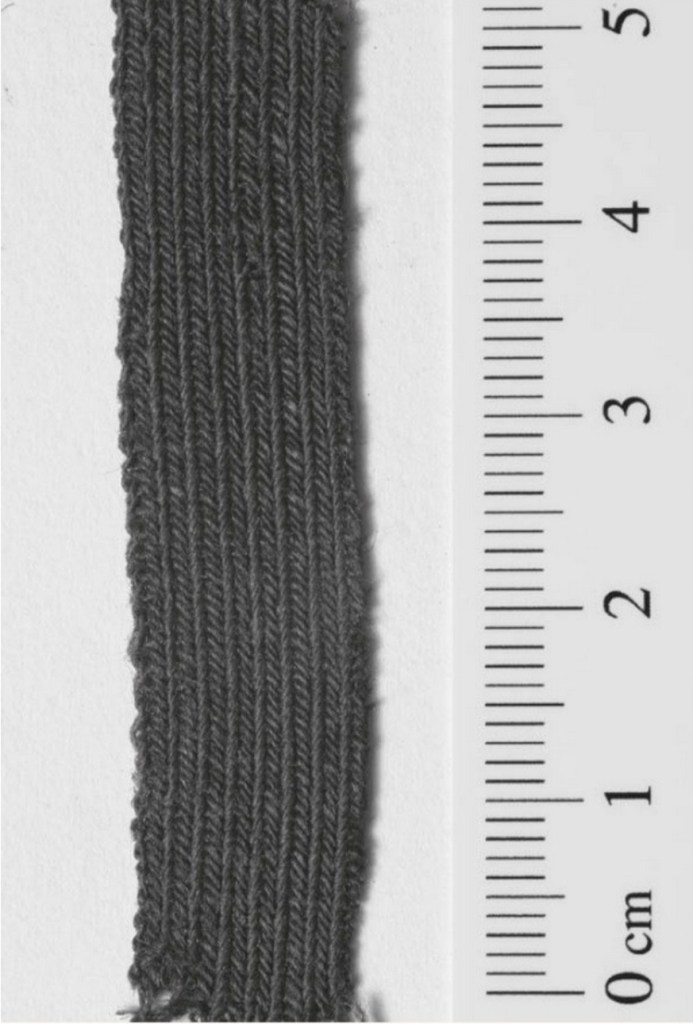

Judith of Flanders, Countess of Northumbria, wife of Tostig Godwinson: @einnstjarna_weaving

Judith of Flanders was born in Bruges in the early 1030s and was known for her intelligence, curiosity, appreciation of beauty, and devotion to her religion. She was the favorite child of her father, Count Baldwin IV, and one of the most beloved princesses in the land. Her father would die when she was very young, leaving her to be raised by her elder half-brother, the new Count of Flanders Baldwin V.

Her appreciation of beauty attracted her to the “handsome as a greek” Tostig Godwinson, earl of Northumbria, who had been exiled to Flanders when his family fell out of favor with the English court. Tostig clearly reciprocated this attraction, so Judith used her wit and influence with her big brother to persuade him to let them marry, despite political objections.

The couple returned to England where they ruled over Northumbria. Judith’s interest in beauty and religion led the couple to donating many gifts to the cathedral at Durham and also supporting churches and monastic foundations across their land.

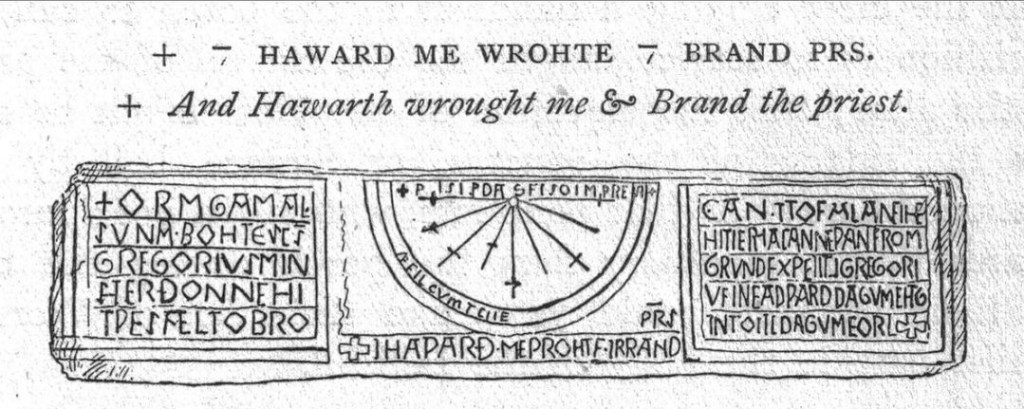

Judith of Flanders became Countess of Northumbria upon her arrival in England and marriage to Tostig Godwinson, Earl of Northumbria. Pictured here is the church in Kirkdale, North Yorkshire that features a sundial with Earl Tostig’s name in dedication. According to the inscription, the church was rebuilt in the mid 11th century, during Judith and Tostig’s rule. Judith was a staunch supporter of the church and beautification projects, and I like to think that she personally supported the rebuilding of this very church, but was overshadowed by her husband with his name being the one in the inscription. IN TOSTI DAGVM EORL (‘in Earl Tostig’s day) Of course….

Judith’s husband, Tostig Godwinson, had difficulty during his earldom over Northumbria. Being a southerner, he was never popular amongst the ruling class made up of Danish invaders and Saxon survivors of these invasions. Tostig ruled with an iron fist which included murdering several family members of Northumbrian ruling class families. A year before the Battle of Hastings, Northumbria rose up in rebellion against Tostig’s rule. Tostig accused his brother Harold of starting this revolt, and he fled once again to Flanders with Judith and their children for safety upon being outlawed again by King Edward the Confessor. He would bide his time in Flanders while procuring allies to take back the North from his brother…

If you know your history, you know that this story doesn’t end well for Tostig. But what about Judith?

Her husband Tostig was killed by his brother’s army at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066.

Judith likely remained in Flanders during this time for her and her childrens’ safety, but not much is written on her in this time period. There is a theory that at least one of her sons fought in the Battle of Stamford Bridge and fled to Norway upon the defeat. Her brother-in-law Harold who had just been responsible for her husband’s death wasn’t able to enjoy his victory; his army immediately began the long march down south to face the Norman invaders led by William the Conqueror. It… did not end well. Perhaps Judith was pleased by Harold’s defeat, especially considering her relation to the French crown, as her niece was Matilda of Flanders, wife to William. Judith never would return to England again in her lifetime.

When reading about battles it is easy to focus only on the men fighting, but it is important to remember that war affected all, men, women, and children. Judith was now alone and faced an uncertain future, and returned to the court of her sick brother. She could consider herself lucky though, as she fared well compared to those who lost their lives in the violence.

Upon returning home to Flanders, Judith’s grief for her husband would have soon been overshadowed by her anxiety for the health of her dear brother. She would spend the next few months quietly in Bruges with her brother, Count Baldwin V, until he passed in 1067.

Judith inherited a relic of the Holy Blood, which had been a gift from Emperor Henry III. This would have been a precious gift to Judith and a reminder of her family, especially as Judith was such a pious woman. Within a year’s time, she lost the majority of her loved ones.

Judith did not seem to desire a second marriage, but political instability led her to accept a proposal from Duke Welf IV of Bavaria. The newly created Duke of Bavaria was a patron of the Weingarten Abbey in Germany, which was fortunate for Judith who loved literature, books, and her faith. She accepted the marriage and in 1070 moved to Weingarten to begin her new life.

Judith of Flanders wed her second husband, Duke Welf IV, around 1070 in a lavish ceremony. This marriage that was done to protect herself luckily flourished, as Judith would find blessings in her new life. Her new husband had just inherited the county of Altdorf in Germany through an uncle. The newlyweds would call the beautiful Weingarten Abbey their home and would have two sons and a daughter together; Welf II, Henry IX, and Kunizza.

Judith’s second family would go on to become the earliest noble house in Germany with a recorded history, and her future descendants would include Henry the Lion and Friedrich Barbarossa.

In Judith’s time, she would live to see her son Welf marry one of the most powerful and distinguished women at the time, Countess Matilda of Tuscany, in 1089. There is a gospel held in the Abbey Monte Cassino with obvious English artwork and a list of German monks that may have been Judith’s wedding gift to Matilda.

Judith would not live to see the marriage dissolved in 1095 when it was discovered that Matilda’s wealth was set to be bequeathed to the church upon her death. Welf II would go on to be the Duke of Bavaria after his father, with Henry IX inheriting the land after his brother’s passing. Henry would be the grandfather of both Henry the Lion and Friedrich Barbarossa, but that’s a different century’s drama.

Gytha of Wessex, younger daughter of Harold Godwinson and Edith the Fair: @eoforwicproject

Gytha of Wessex, born Ēadgyđa Haroldsdōttir, was probably born some time around 1053. Her parents were the future king Harold Godwinson and his common-law wife Edith the Fair. She was just one of many children born to her parents, theirs was a love match.

Gytha was named for her paternal grandmother, the stately Danish noblewoman Gytha Thorkelsdōttir. A relative by marriage of King Cnut, she was quite the trophy wife for Earl Godwin and together they had built a powerful dynasty in 11th century England. We can only guess as to Gytha’s impression of her grandmother, but it’s not unlikely that she set the bar high for what a noblewoman should be.

Gytha the Elder is remembered for her request to William the Conqueror after the Battle of Hastings- she would pay her son Harold’s weight in gold for his body. This was refused, as William recognised the potential for Harold to become an English martyr. He buried him somewhere without a marker, so his burial site wouldn’t become a site for pilgrimage. How would this have made Gytha and the Godwinson children feel?

They didn’t have much time to dwell on their grief. Harold’s heirs were valuable political enemies and William the Conqueror could prevent rebellion by having them in his custody. Gytha the Elder fled and took her grandsons Godwin, Edmund and Magnus first to Exeter and then across the country, avoiding William’s spies and scouts all the way.

At one point after the wintry siege of Exeter (1068), the Godwinson womenfolk were forced to take refuge on the desolate island of Flatholme in the Bristol Channel. Godwin, Edmund and Magnus sailed to Dublin to seek aid from their father’s old friend King Diarmait. After years on the run and several failed Irish-backed raids on the south coast, the brothers finally returned to Flatholme in 1068 or 1069. Their grandmother decided they had no options left but to leave England.

If she was born in 1053, Gytha would have been only 13 years old at the time of her father’s death. At 16 years old, she would leave her homeland, never to return.

In late 1068 or 1069, what remained of the Godwinson family travelled to Saint-Omer in Flanders.

Count Baldwin VI was willing to welcome the womenfolk, as they posed little risk and his aunt Judith had been married to their kinsman Tostig. She may even have been present to welcome the party of exiles. It seems that grandmother Gytha and aunt Gunnhild settled there, perhaps as guests in a religious community.

Harold’s sons, however, were politically problematic. Flanders was allied with William the Conqueror (William’s wife Matilda was Baldwin’s sister!) so hosting his enemies put Baldwin into an uncomfortable situation. Godwin and his siblings left the comfort of Flanders and took to the road once more. Their destination: the court of the Danish king Sweyn.

Godwin and his siblings requested ships from the Danish fleet to launch another invasion attempt of England. Sweyn sympathised with the Godwinson children- he was their father’s first cousin and had also attempted an English invasion himself after 1066. But his bid had been abandoned and Sweyn had accepted danegeld from William to return home. He offered Gytha a different kind of aid.

She received an incredibly plum offer- an arranged marriage to a Prince in the East. This might have seemed like a godsend, as sister to an exile king and daughter to a dead one. But consider too the uncertainty she might have felt. Her whole world had been turned upside down and now, she was being asked to leave what was left of her family.

Gytha’s brothers disappear from the contemporary record after this- it is not known for certain what became of them. Did they come with her or did they start new lives in Denmark?

Like all English noblewomen of the time, Gytha would have been raised a devout Christian, likely with some schooling in the gospels and the psalms. Her aunt Queen Edith had been educated at Wilton Abbey and her youngest sister Gunnhild would follow in her footsteps.

Faith would have been a source of comfort to her and her brothers during these times of hardship and loss, with passages from Psalm 91 taking on a rather poignant tone.

Psalm 91

4 He will cover you with his feathers, and under his wings you will find refuge; his faithfulness will be your shield and rampart.

5 You will not fear the terror of night, nor the arrow that flies by day,

6 nor the pestilence that stalks in the darkness, nor the plague that destroys at midday.

7 A thousand may fall at your side, ten thousand at your right hand, but it will not come near you.

8 You will only observe with your eyes and see the punishment of the wicked.

Gytha met her bridegroom, Volodymyr Monomakh (Володимир Мономах) upon her arrival in Kyivan Rus- an East Slavic state made up of modern Ukraine, Belarus and parts of Russia.

His family line was almost as newly blue-blooded as hers. His father Vsevolod I was a Rus Prince who had won the jackpot when he married a relative of Byzantine emperor Constantine IX Monomachos (Greek for “lone warrior.”) This marriage elevated the Rurikid dynasty Europe and Volodymyr used a Rus version of his maternal family name- Monomakh- to make sure nobody forgot his imperial origins. But he really had no need, as he had already made a name for himself by the time of his marriage.

As Prince of Smolensk, he was a seasoned military man who had fought bravely in several campaigns and made peace with nearby rivals. Similar to Gytha’s father Harold, Volodymyr fit the ideal of Early Medieval masculinity. He rode, hunted, fought and studied diplomacy. Being of a similar age to Gytha (late teens to early 20s) he was also an intensely religious young man who founded several churches and gave generously to religious communities. This makes him sound like quite the Medieval dreamboat, but what did Gytha think of him?

We have no idea. It’s rare for women’s feelings (or indeed anyone’s!) to be recorded in this period and she left behind no diaries or chronicles of her life. Saxo Grammaticus records the marriage some time in the 13th century, but no contemporary Russian sources do. This however doesn’t mean much, as most women are not recorded in the Russian chronicles. Even the name of Volodymyr’s Byzantine mother wasn’t deemed important enough to record!

What is unusual is that Volodymyr himself left us an account of his life. He tells us that his grandmother was a Swedish princess and his father spoke 5 languages. One of these 5 languages would likely have been Norse (due to his Swedish mother’s heritage), which may mean that Volodymyr also spoke it. Gytha was of Anglo-Danish stock and so will have spoken Old Norse too: was this the language of their courtship? Did Gytha ever learn Old East Slavic, the language of many in Kyivan Rus?

The only time Volodymyr mentions Gytha in his account (“The Testament of Volodymyr Monomakh”) is indirectly in his instructions to his sons many years later: “Love your wives, but do not let them rule you.” This might suggest a stern man with little time for the opinions of women- or a wise old ruler who spent decades with a wife who could wrap him around her little finger.

Gytha likely spent much of her lifetime pregnant, nursing or child-rearing. Childbirth poses many risks to mother and child even today and these risks were far greater in Gytha’s time. Many died in childbirth or afterwards from infection. Consider also that Gytha was in a new country and was unlikely to have any family members or friends from home to support her.

Her pregnancies, especially her first, might have been emotionally difficult. The preparations for the new arrival might have reminded her of her own mother and happy childhood in England, what might have seemed an almost impossible distance away. It is also possible that Gytha was delighted- a little prince or princess would complete her new family with Volodymyr and symbolise a new beginning.

Fortune would smile upon Gytha and it seems that she was as fruitful as her mother and paternal grandmother. It is not known for certain which of Volodymyr’s children she gave birth to, but it seems likely that at least 5 of them were hers. The most famous of these is her son Mstyslav I, later known as The Great (b.1076). He would follow in his father’s footsteps as Grand Prince of Kyiv in 1125 and would be the last ruler of a united Rus.

Volodymyr was an active ruler of his lands, but the advice that he left behind for his sons suggests that he was a caring and involved father too. Within a few years of her marriage, Gytha’s home would have been filled with young children and hopefully laughter.

The following children of Volodymyr are believed to have been born of Gytha:

-Mstyslav I of Kyiv

-Izyaslav

-Svyatoslav

-Yaropolk II of Kyiv

-Viacheslav I of Kyiv

-Yurii Dolgorukii (possibly)

Gytha died in either 1098 or 1107. Her passing is not recorded explicitly in any contemporary sources, English or Russian, so these dates are educated guesses. The earlier date (1098) comes from a German source, stating that “Gytha the queen” died that year as a nun. Others have suggested that she died on pilgrimage to Jerusalem, like her paternal uncle Sweyn. If she was born in 1053, then she would have been around 45 in 1098.

There are several fantastical later stories about Gytha’s piety, including her praying over her son Mstyslav after a bear attack. She begged St Pantaleon to intercede and miraculously, Mstyslav recovered. He would later go on to found churches and promote the cult of St Pantaleon in Kyivan Rus, perhaps in his mother’s honour.

The later date (1107) comes from her husband’s own Testament. Volodymyr refers to 1107 as the year of his son Yurii’s mother died. Yurii could also have been mothered by Volodymyr’s second wife (m.1099), but the Russian Primary Chronicle states that Yurii Dolgorukii himself married in 1108. This would make him a young child if he was born to the second wife: an earlier birth attributed to Gytha is therefore more plausible if the Testament and Primary Chronicle are both accurate.

An explanation for this death-date confusion is that Gytha retired to one of her son’s homes or a religious house, allowing Volodymyr to remarry before her death. This wasn’t unheard of among the Rus nobility, as the role of wives was to produce children even into their husbands’ old age. If Gytha went into menopause in the 1090s, she may have chosen to step aside (or indeed have been encouraged to do so.)

Volodymyr had no need to worry about his legacy. He was crowned Grand Prince of Kyiv in 1113 and reigned well until his own death in 1125. He is recognised as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church and is still a popular historical figure in Ukraine and Russia. He is remembered as a sensible, fair and pious ruler who took care of the poor.

Though he did father more children with subsequent wives, it was his sons with Gytha who would inherit the Kyivan throne- first Mstyslav, then Yaropolk, then Viacheslav.

Gytha variously held the titles of Princess of Smolensk, Chernihiv and Pereiaslav at various times through her life. She died before she was able to become Grand Princess of Kyiv, but her legacy is even greater. Through the descendents of her first son Mstyslav the Great, she is the ancestor of all English and British monarchs after Edward III (d.1377.) Her father Harold may have lost his crown, but Gytha made sure their bloodline found its way back to the throne.

Eadgytha Haroldsdōttir of Wessex

Princess of Kyivan Rus, Mother of Kings

1053-1107

RIP

Gunnhild of Wessex (the Younger), younger daughter of Harold Godwinson and Edith the Fair: @skadi.blodauga

Gunnhild of Wessex

Little is known of Gunnhild’s early life, but it seems that she was the youngest daughter of King Harold Godwinson and his common-law wife, Edith (or Eadgifu) the Fair.

As her birth date is unknown, it is possible that she was a young teenager, or perhaps even still an infant, around the time of the Battle of Hastings in 1066. It is likely that she was being raised and educated by nuns at Wilton Abbey, as was common for young high-born women at the time. Wilton Abbey in particular was a key centre of learning, and as the young Gunnhild matured, she may have chosen to remain safely within its walls instead of leaving the convent in the turbulent aftermath of 1066. Many heiresses of the time took refuge in abbeys to avoid marrying into the invading Norman stock, and as the daughter of the previous king, Gunnhild would no doubt have been a prized piece on the marriage market, and a potential political rival.

Nun on the Run

From two extant letters written by Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury, it is clear that Gunnhild eventually did leave the Wilton convent. The exact date is again not known, but it appears that Gunnhild was promised the position of Abbess, but this never transpired (perhaps her aunt, Edith of Wessex/@aelettethesaxon, who was a patron of Wilton, had wanted this, but she sadly died before it occurred). Perhaps feeling shunned, and hearing of the exploits of her sister, Gytha (@eoforwicproject), marrying into a royal family overseas, she felt jealous and sought a more fruitful life, and found it in the form of a handsome Norman landowner, Count Alan Rufus (the Red) of Richmond.

Historian Richard Sharpe has argued that Gunnhild may have left her convent as early as the 1070s. In 1073, Archbishop Lanfranc had ruled that all Anglo-Saxon women who had retreated into a convent at the time of the conquest should choose to either become fully professed nuns, or leave. As Gunnhild was apparently never fully consecrated as a nun, it is possible that she left the monastery at this time. In comparison, the chronicler Oderic Vitalis claims that she eloped with Alan sometime between c.1089-1090, after Alan had apparently come to the abbey seeking to chat up another heiress who was living there, Matilda of Scotland! Since things didn’t work out with Matilda, it seems Alan settled on Gunnhild, and she was seemingly fairly happy to go along with it! But why?

A Norman Husband? (or Two!)

Count Alan Rufus (the Red) of Richmond had fought opposite Gunnhild’s father, Harold Godwinson, at the Battle of Hastings. He was an Anglo-Breton nobleman, probably in his mid-50s, and a companion of William the Conquerer, and is therefore a surprising match for Gunnhild. Or is he? The lands that Alan had been given by William included lands that, before the conquest, had belonged to Gunnhild’s mother, Edith Swanneck (@historywithjess). Perhaps this was a mutually beneficial arrangement – Alan legitimised his claim to these lands by allying himself to the daughter of the previous landowner, and Gunnhild now oversaw her ancestral family holdings.

It has been put forward by historian Richard Sharpe that, if Gunnhild did indeed leave her convent in the 1070s, she and Alan may have had a daughter, Matilda, who became the wife of Walter D’Aincourt. The reasoning for this stems from a headstone discovered in Lincoln Cathedral dated to 1093, which marks the death of William, the son of Walter D’Aincourt, who is described as being of ‘royal stock.’ Walter married a certain Matilda who gave gifts of land to the cathedral. The lands she gave were some of those that, at one time, belonged to Alan Rufus – and how could she have these lands to give, unless she was Alan’s daughter? The evidence for her being Gunnhild’s daughter is sketchy however – there is no direct link, and as Alan was already in his 50s when they met, it is perhaps likely that he already had children, but it is a nice notion that the royal Godwinson bloodline lived on through Gunnhild as well as her siblings.

However, this partnership did not last long – Alan Rufus was dead by 1092. Gunnhild then did the only logical thing, and seemingly eloped with his brother, Alan the Black. However, he too would be dead by 1098, and it was around this time, between 1093-1094, that Gunnhild received admonishing letters from Archbishop Anselm…

“You were the daughter of the King and the Queen. Where are they? They are worms and dust… your loved one who loved you, Count Alan Rufus. Where is he now? Where has that beloved lover of yours gone? Go now, sister, lie down with him on the bed in which he now lies; gather his worms to your bosom; embrace his corpse; press your lips to his naked teeth, for his lips have already been consumed by putrefaction.”

This absolutely brutal extract is taken from one of the two surving letters that Archbishop Anselm sent Gunnhild between 1093-94 (which can be read in all their scathing and fascinating glory on the Epistolae website). Anselm spends the whole letter admonishing Gunnhild for leaving her nunnery – while she was apparently never fully consecrated, he treats her as a lapsed nun. He tells her that God may have killed Alan Rufus because he took her from the convent, and that God may kill Alan the Black too for the same reasons (Alan did die shortly afterwards in 1098), and that she and he will both be damned.

This bullying would undoubtedly have caused deep emotional turmoil within Gunnhild – would she blame herself for the deaths of both men? Anselm fiercely attacks her for leaving the monastery and the religious life she apparently promised to lead, which he says she was marked our for as God’s chosen one. His references to her parents, the now dead King and Queen (@historywithjess), must have been painful. Depending on her age by 1066, it is possible that Gunnhild never really knew her parents, or remembered them little, especially if she was largely raised by the nuns. Perhaps she kept a small token of remembrance – perhaps a coin minted during the short reign of her father, Harold Godwinson. Would she feel guilt for not holding to the religious life and praying for their souls? Would she feel a newfound conflict in her choice of a partner – a man who fought against her father at Hastings, who may have helped kill him? Would she retake her holy vows?

Veiled Once More?

It is unknown if Gunnhild returned to her convent at Wilton. She seems to dissappear from the written record after the death of her second partner, Alan the Black. From his letters, Archbishop Anselm seemed to be under the impression that Gunnhild never actually married either of the brothers, although the reasons for this are uncertain – as I discussed in a previous post, such a match would have been legitimising for both partners. Perhaps it was that Gunnhild was Alan’s (and Alan #2‘s) common law wife, in a similar fashion to how her mother and father, Edith the Fair (@historywithjess) and Harold Godwinson (@mitchofthefyrd), were partners. This set up was not a fully recognised marriage in the eyes of the church, and as someone who had fled the church and was perceived by Anselm to be marked out to lead a religious life, it is almost certain that such a common law marriage between Gunnhild and either Alan would not be recognised, and especially not by a certain sour Archbishop.

However, from the brief contextual evidence that we have for Gunnhild’s later life, I think it likely that she did indeed retake the veil. Anglo-Saxon England was an incredibly pious country, and repeated, severe admonishments by the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Pope’s man in England, would have held huge sway over her thoughts. After Alan the Black died in 1098, the lands passed to a third brother, Stephen. It is unknown if Gunnhild remained with him, but it is equally likely that, perhaps blaming herself for the men’s deaths, just as Anselm had predicted, she relented and retook the holy veil. However, this could have taken a variety of different forms – would she become a vowess or a mynencenu? Or even an anchoress?

Nunne or Mynencenu?

Retaking the veil does not necessarily mean that Gunnhild became (what we might modernly call) a nun once more. There was another type of female religious life available to women at this time too – that of a vowess, or ‘nunne.’

Seemingly dating from the second half of the 10th century, the word ‘mynencenu’ was the female equivalent of ‘munac’, or monk, and thus refers to a woman living a cloistered life in a monastery (now called a nun.) Comparatively, the older word ‘nunne’ somewhat confusingly seems to refer to a woman who had taken holy vows, but had retained her property and continued to live in the outside world as a vowess. Such women were possibly, but not inevitably, widows, and groups of ‘nunnan’ could live together communally, but not in a strictly cloistered way. Instead of retiring to a convent, these women continued living on their estates and oversaw acts of piety and charity. Sometimes, they would be attached to an existing community of monks or nuns (though still living in the outside world), while sometimes they had no affiliated monastic community and worked independently. It has even been suggested by Sarah Foot in her book Veiled Women that a nunne could be the female equivalent of a priest, which is a fascinating thought. For anyone interested in Anglo-Saxon female religious life, I highly recommend her works!

As for Gunnhild, I think either option could have been a viable choice. Having been raised in a convent, she would be no stranger to the cloistered life and may have returned to it. Alternatively, having had a taste of the outside world and all it held, she may have became a consecrated vowess, remaining on her estates in widowhood and living a holy life. I expect either option would have placated sour old Anselm. Perhaps one day more letters will be discovered, telling us of her fate. Her life was seemingly a whirl of grief, relief and turmoil, both in her heart and around her. Her death date is unknown, as she disappears from the written records after the second letter Anslem sent her in 1094, while her second husband died in 1098. I hope that in her later years, she managed to find peace.

Elisiv of Kyiv, Queen of Norway, wife of Harald Hardrada: @hikikomorikikimora

Born into a family of nobles, Elisaveta Yaroslavna (c.1025 – 1067?) was believed to be the eldest daughter of ten (or possibly more) siblings of the Grand Prince, Yaroslav the Wise. Her mother was Princess Ingegerd Olofsdotter of Sweden. Elisaveta and her sisters were believed to be well educated, cultured, and notably beautiful.

It is likely that her first encounter with her future husband was around just 9 years old, when a young Harald Hadrada, a mere 15 years old, fled as a fugitive of King Cnut’s conquest of Norway. Harald and his half-brother, King Óláf, had fought together at the Battle of Stiklestad where Óláf met his demise. Harald eventually settled into the court of Yaroslav in Kyiv, making a strong impression with his skills and military prowess. Even then, young Harald was already asking for her hand in marriage, but he was refused. Whether he was rejected by Elisaveta herself or her father is unknown.

After only a few short years, Harald was off to Constantinople where he would eventually lead the Varangian Guard. During this time, he continued to send riches back home to his future father-in-law in Kyiv. As he amassed more wealth, surely, he was cementing his place in line with Elisaveta’s father as the best suitor. And why not? Her other sisters, young Anne and Anastasia were both married off to maintain alliances as well. Such was often the fate of female nobility; marriages of necessity rather than of love.

My first entry into this series is a rather artistic interpretation of the 11th century fresco of Saint Sophia’s Cathedral in Kyiv known as the “Daughters of Yaroslav the Wise”.

Harald Hadrada returned from his service in Byzantium to Yaroslav’s court in Kyiv, where he had been sending his vast fortune. In 1044, he and Elisaveta were wed. It is often said that Harald was truly in love with her and had not just chosen to marry her for political influence or power, but it is also believed that she did not share the sentiment. Harald wrote poetry about his unrequited affection for his beautiful bride.

Past Sicily’s wide plains we flew,

A dauntless, never-wearied crew;

Our Viking steed rushed through the sea,

As Viking-like fast, fast sailed we.

Never, I think, along this shore

Did Norsemen ever sail before;

Yet to the Kyivan queen, I fear,

My gold-adorned, I am not dear.

Around 1046, the couple relocated to Norway after a brief stint in Sweden. Once in Norway, Harald became “co-king” under Magnus the Good. Magnus maintained a separate court and left Harald to rule Norway while he turned his focus towards Denmark. Elisaveta, known to her Norse subjects as Elisiv or Ellisif, presided over Harald’s court in Norway as Queen.

Within a few of years of arriving in Norway, Elisiv and Harald Hadrada had two daughters, Ingegerd and Maria Haraldsdóttir. Ingegerd, the oldest, was named after her grandmother, Ingegerd Olofsdotter of Sweden. She was probably born around 1046, and Maria around 1048-1049.

After the death of his nephew, Magnus the Good, in 1047, King Harald became the sole ruler of Norway. Clearly, drunk with power, he made the decision to take a second wife, Tora Torbergsdatter, who gave him two sons that would later go on to become kings. You can find Tora here @northseavolva.

One cannot imagine the humiliation Elisiv must have endured knowing she was not the bearer of Harald’s sons and that he openly wed another woman. There were even theories that Ingegerd and Maria were Tora’s daughters instead, but this is unlikely. Young Maria was later engaged to Øystein Orre fra Giske, who would have been her uncle had she been the daughter of Tora.

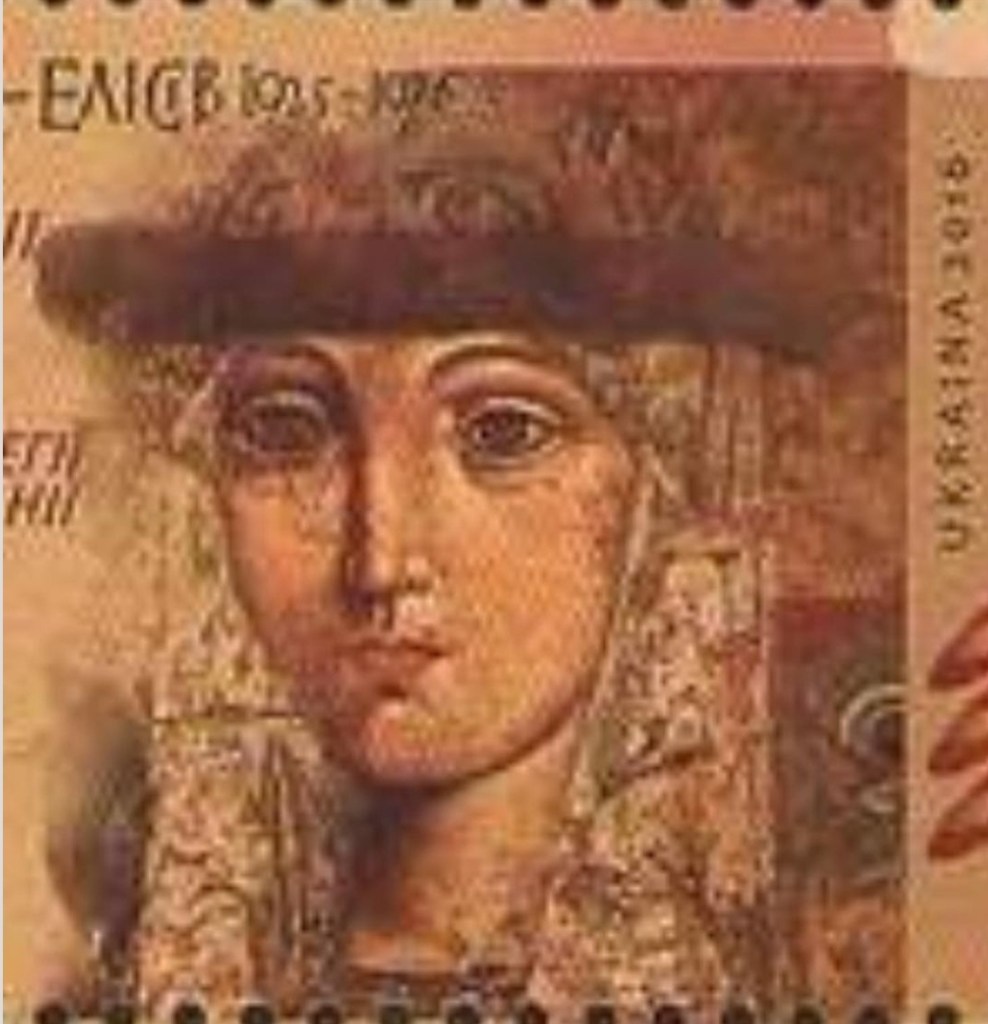

My interpretation of Elisiv is based on a modern image of her from a 2016 Ukrainian stamp, easily found online. Since so few images exist of her, I liked the idea of taking one period image and one from recent times to see how I think she might have actually looked. Note the expression of disappointment.

In 1066, Harald sailed his fleet of over 200 ships to Shetland, and then, to Orkney. He gathered reinforcements for his invasion of England. There has long been confusion as to which wife was left on Orkney and which traveled with him to England. Some sources say Elisiv, as Harald’s wife and queen, would have expected to also become queen of England if he had been successful. The oldest of the sagas claim that it was Tora Torbergsdatter who stayed in Orkney, which is considered more likely, since Tora was the cousin of Thorfinn Sigurdsson, Earl of Orkney. According to Snorri Sturluson, “Thora, the daughter of Thorberg, also remained behind; but he took with him Queen Elisiv and her two daughters, Maria and Ingegerd. Olaf, King Harald’s son, also accompanied his father abroad.”

Unfortunately, Harald was killed in a surprise attack at the Battle of Stamford Bridge. Eystein Orre, Tora’s brother, was also killed. Young Maria, who was promised in marriage to Eystein, reportedly died in Orkney the same day upon hearing of their deaths.

Following these tragic losses, Elisiv, her surviving daughter, and her step-son returned to Norway. Snorri recorded that “Queen Ellisif came from the West with her stepson Olaf and her daughter Ingegerd after her husband was killed.”

Elisiv is presumed to have died in Østlandet the year after she was widowed, although the exact year of her death is unknown. Kyivan princess. Intelligent beauty, who once conquered the heart of the greatest Viking warrior of all time. Ridiculously patient wife. Loving mother. The last true Viking Queen.

Tora Torbergsdatter, second wife of Harald Hardrada: @northseavolva

Tora (Old Norse: Þóra Þorbergsdóttir) was born in 1025 on the beautiful island of Giske, Møre og Romsdal in Norway. She belonged to the powerful Giskeætten, an important clan whose legacy stretched from her father’s leadership all the way into the 1600s.

Her mother was Ragnhild, daughter of king’s man and chieftain Erling Skjalgsson, who fought to defend traditional Norwegian political and religious systems. Her father, Torberg Arnesson, was a chieftain on Giske. He was loyal to King Olav (known now as Saint Olav, one of the most prominent men to christianise Norway), and fought alongside him at the Battle of Stiklestad in 1030.

Tora grew up with two brothers; one became the next leader of Giskeætten. However, she could not have known then that the other would follow her future husband to both of their deaths in 1066.

From her illustrious ancestry and family connections, it’s clear she was a woman destined for great things…

In 1048 at the age of 23, Tora married Harald III of Norway, also known as Harald Hardrada. The reason for this marriage is unknown, yet it was most probably a political alliance. Harald had previously married Elisiv of Kyiv at least 4 years earlier, however it is unknown if she was in Norway at this time.

Whatever the circumstances, the marriage propelled Tora into a queen-like role in Norway and certainly raised her family to a higher status. This benefited Harald as well, as Tora’s family was one of the most politically powerful in the country.

Their union strengthened the royal family’s sociopolitical power in Norway, creating a relationship which cemented the future of medieval Scandinavian royalty…

After Tora’s marriage to Harald Hardrada, she gave birth to two sons: Magnus in 1048 and Olav in 1050. Both of them would come to rule Norway together as kings after the battles of 1066, known then as Olav III and Magnus II respectively. Magnus ascended to the throne the year before his brother joined him but died in 1069 at only about 21 years old. However, Olav would go on to marry and continue the family tree, ensuring an heir to the throne.

Tora’s legacy may not be recorded in detail within sagas or history books, however through her union, she gave birth to a powerful bloodline which shaped the course of Norwegian history.

Matilda of Flanders, Queen of England, wife of William the Conqueror: @rowena_cottage_costuming

Matilda of Flanders (c.1031 – 1083) was many things throughout her life:

Granddaughter to the King of France

Daughter to the Count of Flanders

Wife to the Duke of Normandy and eventual King of England

Mother to at least 9 children who survived into adulthood

But Matilda was also a hugely influential woman, due to her legitimate noble birth, she was much higher in station and influence than her husband for a large part of their marriage, and was a powerhouse in politics where she often stood as regent for both the Dukedom of Normandy and the Crown of England.

The “Rough Wooing” of Matilda of Flanders began in around 1050/1051 when William, Duke of Normandy’s proposal of marriage was initially declined by Matilda’s family. There are several possibilities for this refusal, one being that William and Matilda, like many proposed matches of the time, were related by blood. They were third cousins once removed and thus were too closely related for the Pope to consider allowing such a union.

Matilda was also a member of the nobility, and was of royal descent on both sides of her family tree. She was a descendant of the House of Wessex as a 5x great grandchild of the Anglo-Saxon King, Alfred the Great, and a descendant of the House of Capet as the granddaughter to the King of France, Robert II. In addition to her royal pedigree, she was also legitimate, placing her higher in station to William. Whilst being a duke, William was not the legitimate heir to his Dukedom when he inherited it at the age of 8 years old, and by some accounts, may have held onto his title as a child by sheer luck.

Chronicles and stories from the time all seem to agree that William travelled to see Matilda in protest of his denied proposal, and left with a promise of marriage. What isn’t always agreed on is how this occurred. The first part of the prevailing story is depicted here.

Chronicles and stories from the time all seem to agree that William travelled to see Matilda in protest of his denied proposal, and left with a promise of marriage. After Matilda recovered from her *encounter* with William, whatever form that actually took, it seems that she then declared she would marry no other man than he, and would entertain no other proposals for her hand. Matilda and William were married at age 20, and 24, respectively, in around 1051. Papal dispensation for the consanguinity of their marriage was not granted until 8 years later, in 1059. William and Matilda were required to pay for the founding of 2 churches in recompense.

A supposition: As a wealthy noble woman, Matilda may have had some kind of holy relic which she kept about her person, for comfort and guidance from God. Matilda’s grandfather, King Robert II of France travelled to Rome in 1009 or 1010, roughly the same time her mother was born, to try and obtain his third (yes, third) annulment from the Pope. It is said that whilst there, a saintly vision appeared to him and he swiftly returned to France, where he then had at least 2 more sons with his Queen, Constance of Arles.

Depicting here, I am supposing that King Robert may have brought back a holy relic from his trip to Rome and given it to his wife, who then may have passed it to her daughter Adela, when she went to marry Baldwin, Count of Flanders. Adela may have then given such a relic to Matilda for guidance, when she was struggling with her own marital decisions.

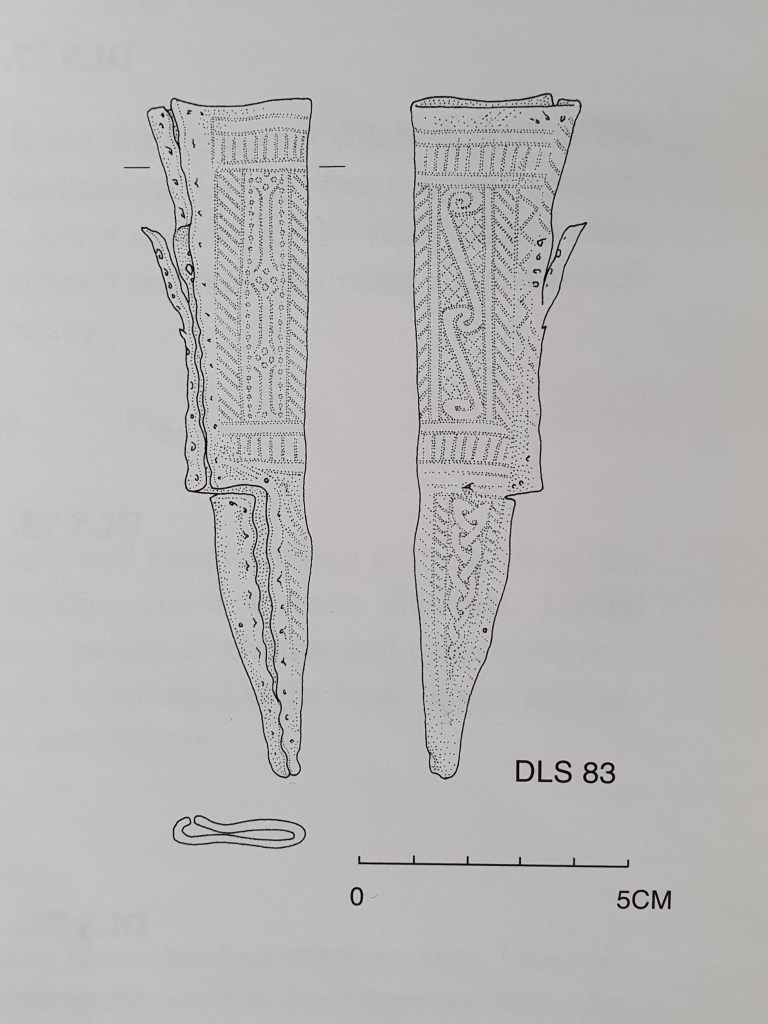

The relic used here is a to-scale copy of a reliquary found in York.

Photo credit to @countrysidecaptured with @rowena_cottage_costuming and @eoforwicproject (models.)

Matilda Regina

Matilda was crowned Queen of England on 11th may 1068 during the feast of the Pentecost. While she is often referred to as England’s first Queen, we know from history she is actually the first Queen of “modern” England, post conquest. She was however, the first Queen to have such a public coronation and the first to be crowned in Westminster Abbey.

The ceremony was conducted in a way so as to demonstrate her power as a Queen, not simply as the wife of a King. Here was a woman with her own power and prestige, who not only shared the royal authority of her husband but who was already trusted to act in his stead.

Matilda brought legitimate royal blood to the throne of England. By affording her a coronation separate to his own, William was using Matilda’s status to bolster his own rule. This was something a future King of England would also successfully manage, when someone else not technically or legitimately in line for the throne, King Henry VII married Princess Elizabeth of York in 1486. In that instance, Henry had to hold a double coronation with his Queen in 1487, to show that his rule was a united front between the houses of Lancaster and York. Here was another King who won his throne by combat but needed an important and influential woman to help him hold it.

Only a few short accounts of the event exist today, however, all seem to agree that Matilda’s coronation was a spectacle of grandeur and chants created for this occasion were recited for her. There are no contemporary depictions of the coronation. Using creative licence, Matilda is depicted as per an 1850 statue in Paris.

Only a few short accounts of Matilda’s coronation exist, however, given the importance of the general populace accepting the new rule in England, it must have been a very affluent affair.

William was a foreign born king solely by right of conquest, who had no real ties to England, whereas Matilda was granddaughter to the king of France, and a descendant of the royal House of Wessex. William would have been keen to emphasise these connections to bolster his own position of power.

By giving Matilda her own coronation, this would emphasise to the English nobility particularly, those people who could have the power to dethrone William if they so chose to. That Matilda’s position was that of a queen, appointed by God, not simply as the wife of the king.

This was not the first, or last time, that a man would use a well connected woman to gain, seize, or hold, power in England.

While there are no contemporary depictions of the coronation, we can suppose what Matilda could have looked like, based on the fashions of the time.

The Passing of the Torch (or the Crown?)

In 1080, a Princess of Scotland was born and was named Edith of Dunfermline. She was baptised that same year and had 2 Godparents. The first was Robert Curthose, who was the eldest son of her second Godparent, Matilda of Flanders, England’s Queen, and her husband William.

Legend goes that at the baptismal font, the young baby Edith pulled on Matilda’s headdress causing it to fall onto her, this was seen as a sign that she would one day become a Queen. This would eventually come true, when she married Matilda’s third son, Henry Beauclerc only a few short months after he became King of England.

Edith Married Henry I in November 1100 and was crowned as Queen of England at the end of the wedding ceremony. She took the Regnal name of Matilda, likely to please her Norman husband and subjects. Edith is also likely to have chosen this name as a way of honouring her late Mother in Law, and Godmother, Matilda, who had died some 17 years previous.

Edith was a Princess of Scotland and also a member of the Royal House of Wessex as the daughter of King Malcolm III and Margaret of Wessex, Queen of Scotland (who was Canonised as a Saint in 1250).

In this union we see another Norman King of England using a descendant of the House of Wessex to help legitimise and secure his rule. A direct mirroring of William and Matilda’s situation.

Edith is often remembered under such epitaphs as Matilda the Good Queen, Good Queen Maud, or Matilda of Blessed Memory.

She was the mother of Empress Matilda, the disputed Lady of the English who failed to successfully inherit the throne from Henry upon his death in 1135.

It has been 941 years since the death of Matilda of Flanders, Duchess of Normandy and Queen of England. Matilda died in Normandy at around age 52, and was interred as per her wishes, in the Abbaye-aux-Dames in Caen, which was founded by William and Matilda when they married.

Matilda the Daughter

Matilda the Wife

Matilda the Duchess

Matilda the Queen

Matilda the Mother of Kings

Matilda of Flanders, 1031 – 1083.

What a Life

What a Woman

What a Legacy!

(NEW FOR 2024!) Gytha Thorkelsdōttir, Countess of Wessex, mother of Harold, Tostig, Queen Edith, Gunnhild (the Elder), wife to Godwin: @paulaloftingwilcox

Building A Dynasty

Gytha Thorkelsdottir was born at the end of the 10th century, around 997. She was the daughter of a wealthy Danish magnate, Thorkel Sprakalegg, who also fathered her brothers Ulf and Eileifr. Thorkel doesn’t seem to have been the shy retiring type- he features in several sagas (where he is said to be the product of a union between a noblewoman and a bear) and forged some politically-excellent marriages for his children. His eldest son Ulf would marry Estrid, daughter of the Danish King Sweyn Forkbeard and sister of King Cnut. He accompanied Cnut on his invasion of England and became one of his most trusted nobles. Another rising star at the English court of Cnut would marry into Thorkel’s family: Earl Godwin.

Godwin may well have seen Gytha as the ultimate trophy wife- she was a wealthy aristocrat and while not a royal by blood, she was seen as kin to King Cnut through her brother’s marriage. Gytha and Godwin were probably wed between 1022-23, after Godwin had proven himself as an Earl for around five years. It seems as though they were a great match, with Godwin being an ambitious politician and later a “kingmaker” figure and Gytha a confident matriarch and stalwart supporter of her husband.

Together, they would prove extremely fruitful, with at least 9 children being named in the historical record. Of their sons, the eldest would be Sweyn, followed by Harold, Tostig, Gyrth, Leofwine and Wulfnoth. Their daughters were future queen Edith (originally called Gytha, after her mother), Gunnhild and Ælfgifu. It seems that most of their offspring inherited Godwin’s boldness: trouble was never far behind the Godwinson clan with Godwin and several of their sons being exiled on numerous occasions! However, they also flourished. Most of their sons received earldoms and the family owned vast estates across England. Gytha also arranged some exceptional matches for her children, with Tostig marrying the wealthy Flemish heiress Judith and Edith (not to be outdone) becoming Edward the Confessor’s queen.

Sadly, Godwin passed away in 1053. This must have been incredibly hard on Gytha, but she took solace in her children and the running their estates. By the time of Harold’s coronation, Gytha was a grandmother and she may have felt that her family’s legacy was secured.

Mother of Heroes

On the 14th of October, Gytha’s world was turned upside down. She would lose three sons at Senlac Hill, Gyrth, Leofwine and their own King Harold. While the political implications were dire, I have no doubt that Gytha mourned the loss of Harold and his brothers simply and profoundly as a mother. Tostig had been lost to her since his defection to the Norwegian army, Sweyn too had died in disgrace a decade before returning from pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Her little boy Wulfnoth, now a young man, had been given as a child hostage years before and was still kept prisoner in Normandy. Her daughters were all childless and Harold’s children, promised a royal life, were now as good as orphaned.

Did Gytha weep? Did she stagger and scream when she heard of her sons’ fate? Or did she stoically bear the heartbreak, locking away her grief where only she knew it? We don’t know. William of Poitiers in his account of the Conqueror’s life claims that Gytha offered Harold’s weight in gold to William in order to receive his body. This was denied and so was her ability to give her sons a proper burial.

We have no confirmation of where Gytha was when she received the news, nor who she was with. We have interpreted a dramatic but in some ways kinder view, where Gytha accompanies her daughter-in-law Edith the Fair to Senlac Hill, with her vowess daughter Gunnhild as spiritual and emotional support.

The Wives of Many Good Men

Not one to take things lying down, Gytha channelled her strength into rebellion. After her requests of William were denied, she hastily fled with her household and several of Harold’s children (probably including her namesake granddaughter Gytha the Younger.) They ventured across southern England trying to drum up support for their cause and avoid capture, followed closely by William’s agents. Gytha settled for a time at Exeter, a town with a strong anti-Norman sentiment. She still held a great degree of sway with the remaining English nobility and she used it to her advantage. While Harold’s sons sailed to Ireland seeking mercenary support, chronicler Orderic Vitalis states that Gytha sent word to any settlements she could in the region, urging them to defy Norman rule and support her grandsons. He also notes that she asked her nephew, now King Sweyn II of Denmark, for aid.

Unfortunately for Gytha, Exeter would prove a disappointment. Her grandsons took much longer to return from Ireland than she hoped, her nephew Sweyn refused to send troops and William won the city in early 1068 after 18 days of siege. Faced with absolute destruction, the people of Exeter accepted his rule and begged for clemency. Gytha and her party escaped Exeter by ship and set up camp discreetly on Flat Holm, a small estuarine island in the Bristol Channel. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes Gytha as being in the company of “the wives of many good men” (“manegra godra manna wif”.) They may have waited there for months, waiting for the return of Harold’s sons’ fleet with Hiberno-Scandinavian mercenaries.

Perhaps the wait was too long or the conditions on Flat Holm became too arduous, but we know that Gytha and Gunnhild fled England for the final time with their companions in 1068. They took shelter in Saint-Omer in Flanders, a town familiar to the Godwinson family. Perhaps Edith the Fair was with them- her eldest children likely were- and with no husband and her vast estates all confiscated, England was not safe for her either.

Life and Death in Exile

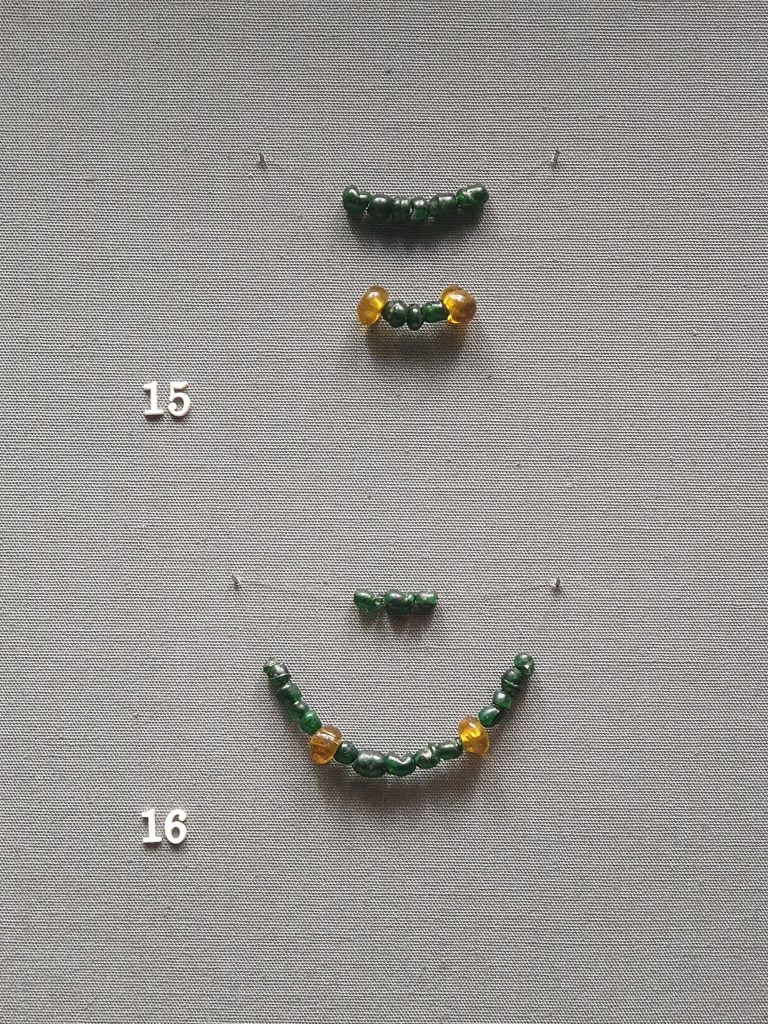

Though Gytha and her household were forced to leave their homeland, they did not leave totally empty-handed. A huge amount of the family wealth was portable and it’s believed that Gytha took all she could when the victorious Normans advanced. It was from these coffers of gold, silver and precious relics that Gytha offered William her bribe for Harold’s body. They also funded the ships and fierce Irish mercenaries that accompanied her grandsons on their raids. It’s possible that the Godwinson Hoard may have even contained Harold’s crown: a crown gifted by “Lady Gunnhild” shows up in Bruges’ St Donation’s records, along with lots of treasure and an ornamented gospel written in Old English (the canons note that none of them can read it!) These financial reserves provided Gytha and her family with some security in their exile- many religious institutions would be happy to provide hospitality to wealthy patrons and their households, with the expectation of donations.

This was no issue, as Gytha was generous to the Church even prior to the Conquest. The 12th century Warenne Chronicle describes Gytha’s piety. “Moreover his (Godwin’s) wife walked a path of great sanctity and abundant religion, and every day she zealously heard at least two masses and almost every Sabbath she walked two or more miles on bare feet to nearby monasteries, piling up generous donations on the altars and refreshing the poor with generous gifts.” Despite this coming from a Norman source, it shows that she was later remembered as being one of the virtuous Godwinsons (like her daughters Queen Edith and exiled Gunnhild, unlike her upstart sons Harold and Tostig.) We know that Gytha died within a few years of her move to Saint-Omer and she was likely buried there. She was survived by her daughter Gunnhild, who likely inherited the Godwinson Hoard from Gytha and remained in Flanders throughout most of her life. We can hope that Gytha’s final years were peaceful and that she was able to find some comfort in her good works, prayer and the companionship of her daughter.

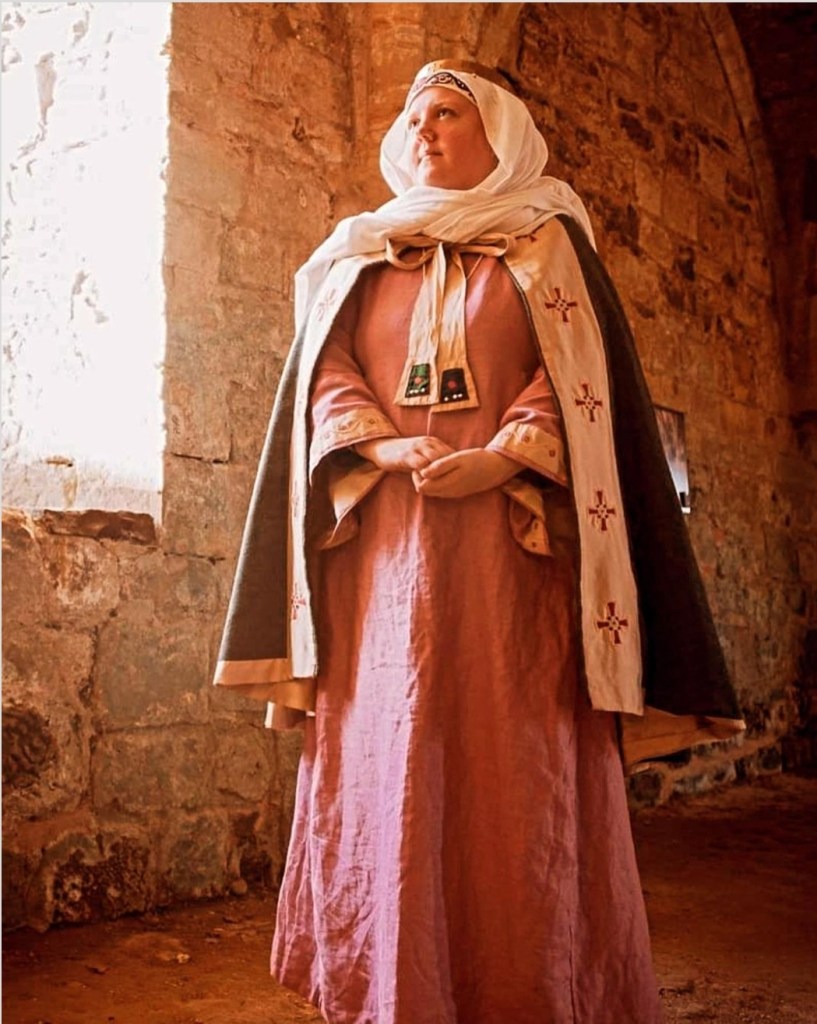

(NEW FOR 2024!) Edith of Mercia, second wife of Harold Godwinson, former Queen of Wales: @daisydrawsbad

Queen of Wales

Edith of Mercia, known variously in sources from her time as Ealdgyth or Aldgyth, was born at some time in the first half of the 11th century. Like so much of her life, her exact birthdate is unknown. Her father was English nobleman Ælfgar, himself the son of Earl Leofric of Mercia and a certain Godgifu (known today as Lady Godiva!) On her father’s side, Edith came from a large and wealthy noble family with a reputation for good deeds and piety. Far from her legendary nude antics, the real Godgifu and her husband the Earl founded many religious houses, gifted a great many treasures to the Church and had nine children. Busy folks! Just like their contemporaries (and rivals) the Godwinsons, Edith’s family were active players in the royal courts of 11th century England and vied for position and favour.

We know that Edith was a recognised child of her father Ælfgar and that she had two brothers, Edwin and Morcar- these two brothers would become famous in their own right at 1066’s Battle of Fulford. We can assume that Ælfgar’s wife Ælfgifu was their mother and that the siblings were born and raised in England. Judging by the approximate dates of her father’s birth and her own marriage, we can also assume that Edith was born some time between c. 1035-1045.

Similar to the Godwinsons, Edith’s family life was not always plain sailing. Upon the Godwinsons’ exile in the early 1050s, her father Ælfgar had received Harold Godwinson’s earldom of East Anglia. But in 1055, her father Ælfgar was exiled by King Edward the Confessor for treason- the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes him as being outlawed “without any fault”. We don’t know if the charges were actually substantiated or even if his family accompanied him abroad, but it’s likely that this event affected his wife and children deeply. The political backstabbing of noble circles and the uncertainty of the Crown’s changing whims must have made for very anxious formative years. Fortunately, during his time in exile in Ireland, Ælfgar befriended an important ally: Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, King of Wales.

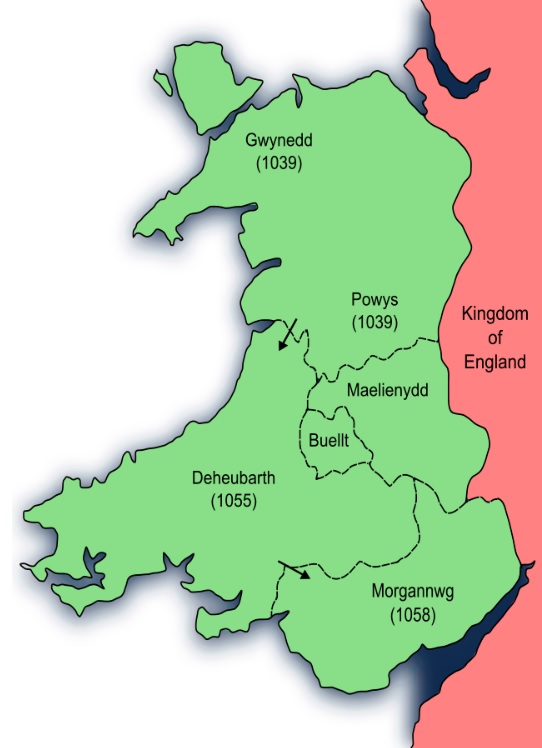

Gruffydd was a Welsh nobleman and fierce conqueror of his own: previously King of Gwynedd and Powys, he had just that year become ruler of all Wales. He was the first and last man to ever rule as king of a united Wales and he achieved that through ruthless military campaigns and a dogged resilience to dominate. It was such a man who would change the course of Edith’s life.

Edith’s father Ælfgar accompanied Gruffydd with Hiberno-Scandinavian mercenaries on a raid on Hereford, razing it and forcing Edward the Confessor to discuss terms. Amusingly, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes events thus: “And then when they had done most harm, it was decided to reinstate Earl Ælfgar.” Peace was restored, with Gruffydd returning to Wales and Ælfgar being allowed back to England. Ælfgar was once again Earl of East Anglia, but in 1057, his father Leofric died and passed on his Earldom of Mercia to him. Edith, while likely saddened by her grandfather’s passing, may have been cautiously optimistic for her family’s future. Historians believe that it was upon her father’s inheritance of the Earldom of Mercia in 1057 that he arranged her marriage to his ally, King Gruffydd.

Her bridegroom was almost certainly her senior- he could have been born as early as 1010. If we place Edith’s birth conservatively in the late 1030s, then she was in her late teens when she married the war-hardened middle-aged Gruffydd. Of course, she could have been older or even younger- all we know is that she was considered to be of an acceptable age to marry in 1057.

We have little contemporary evidence of their married life together, but it seems to have been a fairly successful one. Edith bore him a daughter named Nest and she may also have been the mother of Gruffydd’s sons Maredudd and Idwal. Wales was relatively peaceful under Gruffydd’s rule: he had defeated all of his rivals and asserted himself to his neighbours as a force to be reckoned with, at least for the time being. Dr Mike Davies (author of The Last King of Wales) describes him as being fabulously wealthy, with a fleet of ships and his flagship being crowned with a golden prow. He patronised a court poet and held court at Rhuddlan. Norman chroniclers noted Edith’s appearance- the near contemporary William of Jumièges describes Edith as a very beautiful woman (though he is unlikely to have ever met her) and the 12th century Walter Map describes a gorgeous woman “much beloved by” Gruffydd at his court- traditionally historians have taken this as a reference to Edith.

As for how Edith herself felt about her new life as Queen of the Welsh, we don’t know. It must have been daunting to live in a new country, especially when separated from her family for the first time and carrying with her their expectations. But then again, she may have been excited to start her own family and live not just as a free married lady but as a queen to a powerful king.

Peaceweaver

Sadly for Edith, the new life she had built in Wales was soon to come crashing down around her. Her father Ælfgar had done much to maintain the truce between Edward the Confessor and Gruffydd: something that the rival Godwinson family did not support. The political history of this relationship is extremely complicated and goes back decades, but put extremely simply, Harold Godwinson had a major score to settle with Gruffydd. This is despite the fact that his elder brother Sweyn had been good friends with Gruffydd, enough so that Sweyn had helped him win a large portion of his kingdom (before his exile “for life” from England, for carrying off the Abbess of Leominster.) Perhaps Gruffydd’s affinity for the Godwinson clan’s embarassing eldest son wound up Harold, more likely it was the years of raids on English border regions and the sacking of Harold’s own Hereford in 1055. In any case, there was bad blood and the Godwinsons were eager to strike back at the Welsh king.

They would get their chance in 1062, when Ælfgar died. Edith, no doubt reeling from the death of her father, would shortly receive another blow. Without her father’s mediating presence, Edward the Confessor granted Harold permission to launch an attack on Gruffydd’s court in the winter of 1062. We don’t know where Edith and her children were when the English forces attacked, but Gruffydd is said to have escaped by the skin of his teeth on a ship.