Location: Jorvík (York), England

Date: Mid to late 10th Century

Culture: Anglo Scandinavian

Estimated Social Class: Middle, wealthy urban

This will hopefully be the first of several speculative York impressions, built to showcase various artefacts and show how they potentially could have been worn/used in their day. It is not based on a grave nor is it to be taken as absolutely representative of the fashion of the place and time. My aim is to show a sensible and plausible outfit based on contemporary artefacts unearthed across York and give context to those remains and fragments.

Excuse my modern garden backgrounds, my 10th century longhouse was in the wash.

Starting from top to bottom:

Headscarf

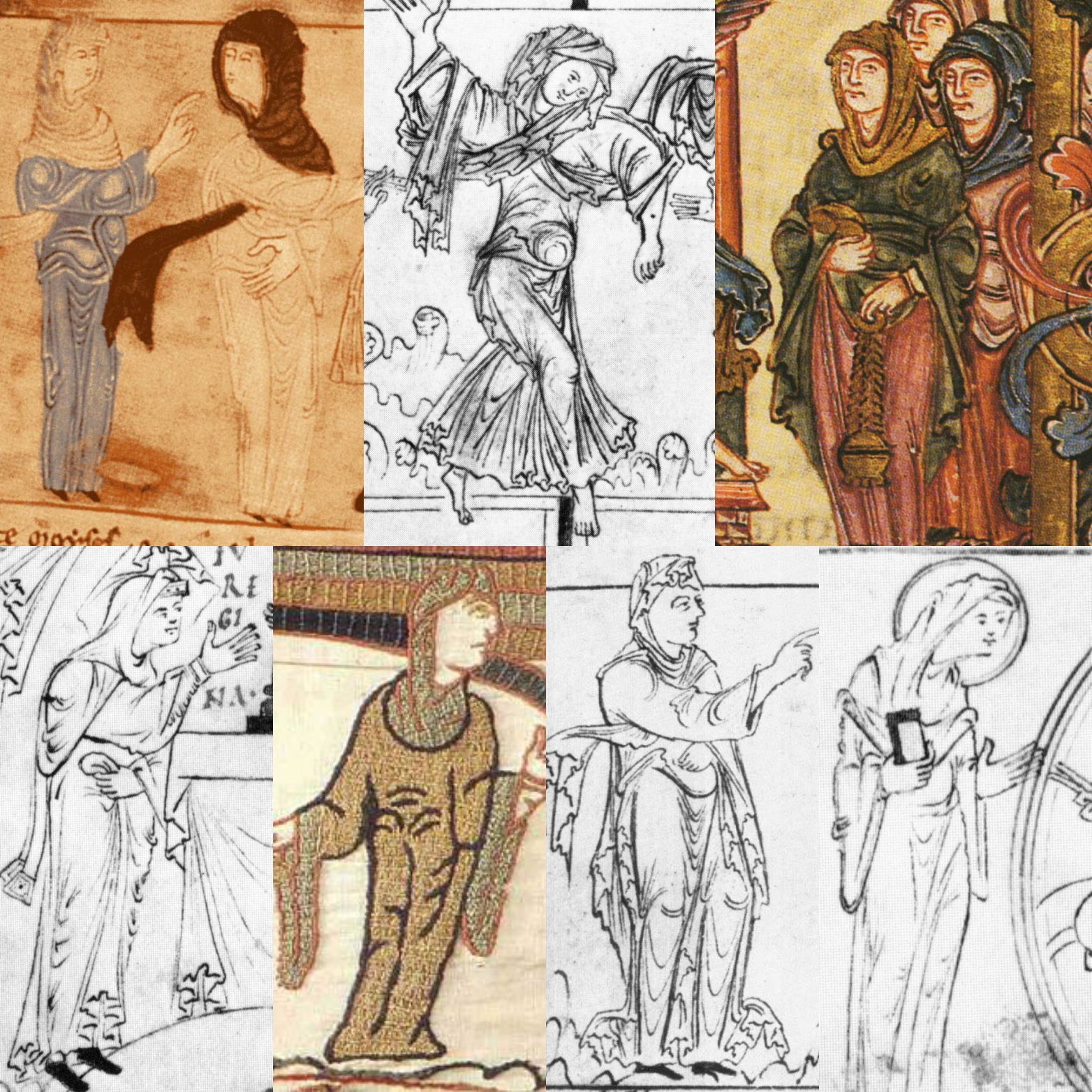

My veil is a plain weave, pale blue wool scarf. It is not naturally dyed, but in shade it closely mimicks woad. Women are almost exclusively portrayed veiled in Early Medieval English art, yet few examples of such veils are represented in the archaeological record. Fine woollen scarves with tassels have been found in Dublin, dating to the early 10th to mid 11th centuries (Wincott Heckett, 2003, pp.9-43). My veil is closer in size to the larger examples found at VA Dublin, such as the silk scarf DHC17 from Fishamble Street (dated to the early 11th century) but matches most closely with contemporary English manuscript depictions in size.

I wear this scarf several different ways even within the same day, tossing the ends over my shoulders as and when it’s required. The weather was balmy when I took these photos, so pins and a fillet weren’t needed. On windier days or if I’m feeling a little more haughty and austere, I’ll pin my veil onto a cap worn underneath and sometimes a fillet. Period variation in wimple/veil style is supported by English manuscript depictions, which show several different styles were worn. Presumably this was down to preference, though of course it could be an indicator of class or piety.

I could talk all day long about headcoverings, suffice to say that I will cover them in greater detail in a future post if people wish.

Necklace of amber and jet

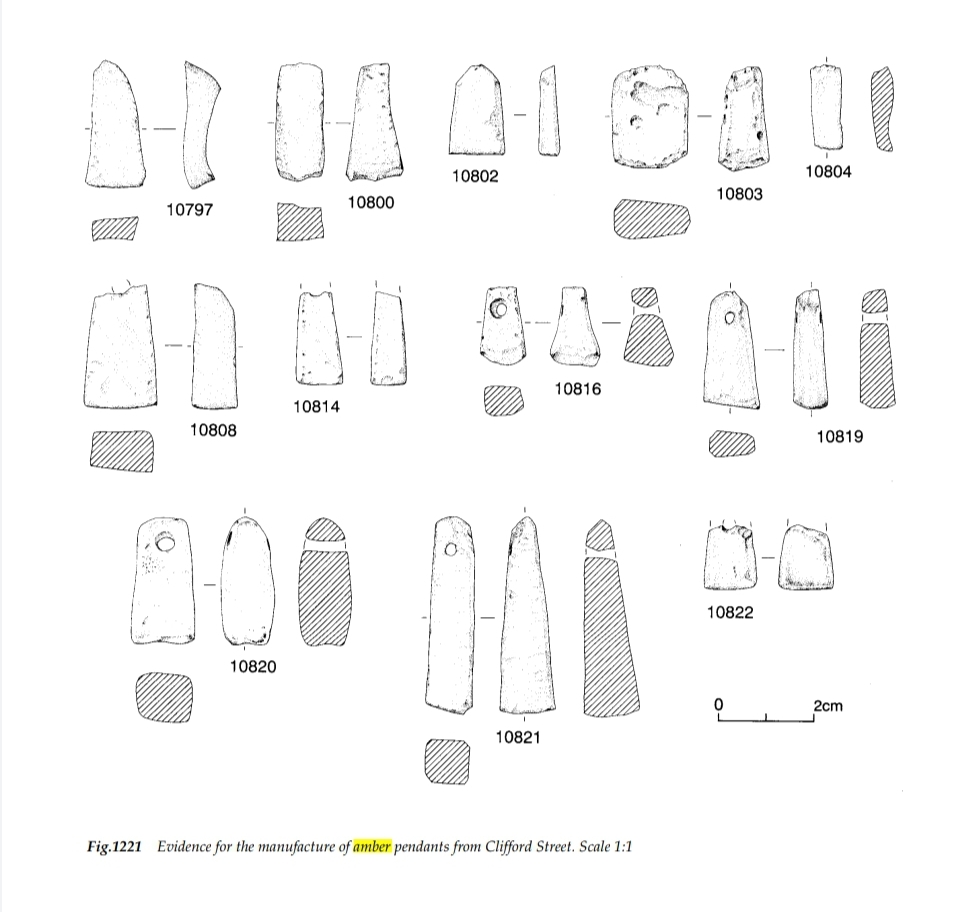

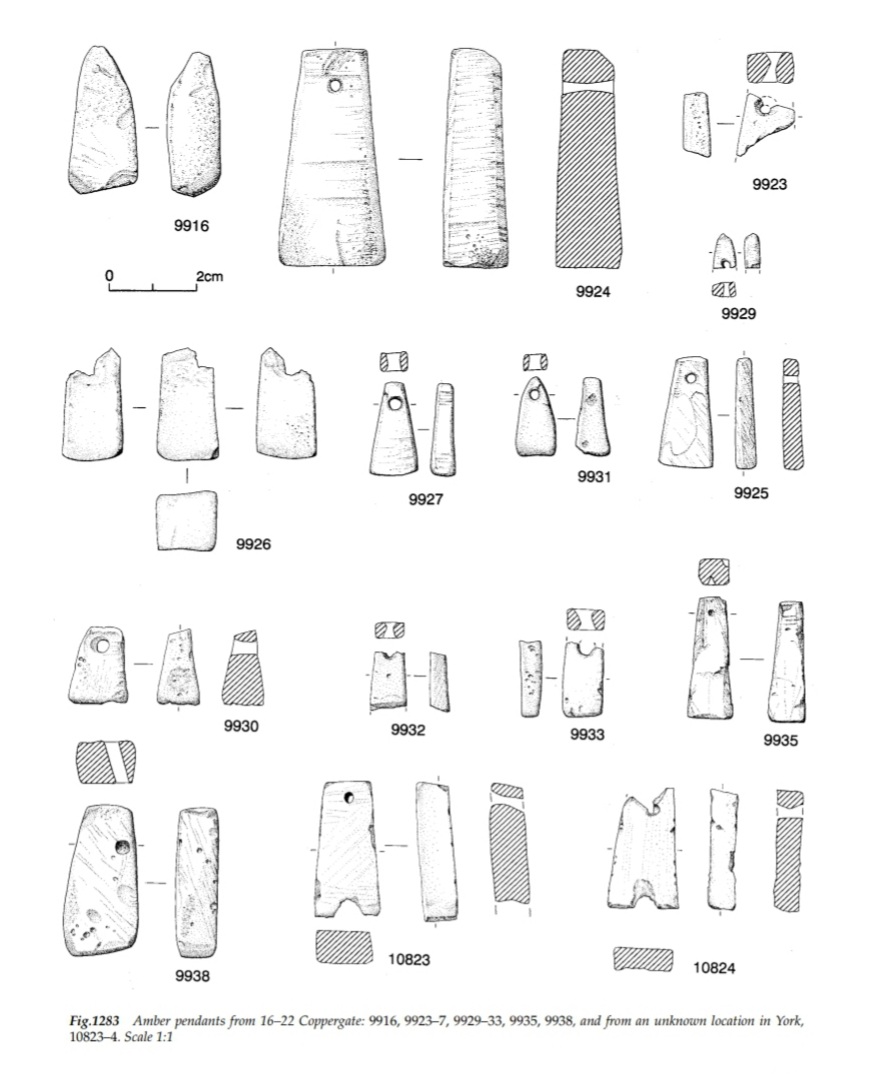

My necklace is made up of amber and jet, based on pendants and beads found at 16-22 Coppergate and other nearby sites. Extensive evidence for amber working in York was found at Clifford Street and 16-22 Coppergate, with fragments also being found at 22 Piccadilly and elsewhere on the Coppergate site (Mainman and Rogers, 2000). The wedge-shaped pendants I used are a little more rounded than the originals, but they can be replaced as and when I find a gemologist who will make me a more accurate replica. 😁 Many of the amber beads and pendants found at 16-22 Coppergate were dated to period 4B (c.930/5-c.975 AD.)

The evidence for jet working at 16-22 Coppergate is definite, whether or not that evidence belongs to the Anglo-Scandinavian period is a subject of debate. Some items were found in Anglo-Scandinavian levels, but it has been argued that they were Roman items that ended up deposited in later levels through the passage of time. It does however remain possible that some of these jet items were indeed stratified correctly and I am working with that assumption.

The beads I used for my necklace are Whitby jet, dating to the late Victorian or early Edwardian period. They’d been reassembled into a new modern necklace, so I liberated them and used them for this project. Like their amber brethren, they are not perfect- they’re a little too spherical and neat. The jet finds from York consist of finger rings, bracelets, gaming pieces, pendants and manufacturing evidence (Mainman and Rogers, 2000). There was also an item identified as a bead (dated to the 5A period, approx 975 AD) but unfortunately it was stolen. I have included my beads in this impression based on the semi-worked fragments, the lost bead and the similar beads found in glass, amber and other materials.

Dress

My dress is made of a 2/2 chevron (herringbone) twill wool. I’ve dyed lots of wool blue using woad, but not this wool- it is chemically-dyed mimicking shades of a natural woad vat. It is handsewn by me with wool and linen thread. Textile fragments of broken chevron twill dyed with indigotin (the blue colour compound found in woad) were found at Coppergate, item number 1302 (Walton, 1989). The material was dated to period 4B, indicating a date of c.930/5-c.975 AD. It is described it thus:

“Fragments, largest 140 x 100mm, of mid brown 2/2 chevron twill, 8/Z/0.9 x 5-6/S/1.2 (Fig.134a). Yarn soft and unevenly spun. Fleece type, Z medium, S hairy. Dyed with indigotin. Hard concretions containing cess-like material adhere to parts of the textile.” (Walton, 1989)

In all the surviving textiles from Anglo-Scandinavian Jorvík, woad is represented but it is not the most common dyestuff. Madder- and bedstraw-dyed fragments are the most numerous by leaps and bounds, which indicates a distinctly English taste in Anglo Scandinavian York (I’ll discuss this at more length in a future article.) Woad however certainly did feature in the clothing of Jorvík city dwellers and I just so happened to have some suitable fabric leftover from a dress made for a dear friend many moons ago. Being a Yorkshire lass through and through, regardless of the century, I was using it.

No complete or near-complete garments have survived from Jorvík apart from the famous sock and several head-coverings. I therefore kept the pattern of my dress and undertunic as generic as possible. Women in contemporary English art are always shown wearing ankle length, long-sleeved garments, usually with some indication of skirted construction. It is believed that this might have been the case in Scandinavia too, with women in contemporary art there usually being shown to wear garments that are at least longer than men’s (Ewing, 2007).

Towards the end of the Viking Age in England, the sleeves on women’s overgarments appear to have grown wider, with tight-sleeeved garments being seen peeking from underneath them. I kept the sleeves on my dress relatively close to the arm so it would be more suitable for earlier impressions, with the opportunity to dress it up later with the simple addition of a mantle or baggier-sleeved overdress.

It is also prudent to note that almost all of the women portrayed in contemporary English art were very high in social status or were religious figures. They represent an ideal of the most aristocratic and modest women, not the daughters and wives of merchants (even wealthy ones) who might have walked through Coppergate. So, my York lady may well have worn her dresses with baggier sleeves on special occasions but likely not to go to the market.

Surviving remains of skirted tunics such as the Skjoldehamn, Haithabu and later Herjolfsnes finds show examples of how these women’s garments in the Viking Age could have been constructed. Due to cloth constraints and to better fit my body, I opted for bottle-shaped side gores starting at my underarm. This construction provided the correct period silhouette while remaining comfortable.

My undertunic (or serk) was made in a similar pattern, only in undyed linen with a plain round neckline and triangular gores.

Leather belt with dyed bone buckle

Over my dress, I wear a belt of dyed bone buckle. This is an unusual item, currently kept in the Yorkshire Museum. The museum lists it only as Anglo-Scandinavian and dating to between 866 and 1066. It is generally believed that Early Medieval women did not wear leather belts, either opting for textile belts that have rotted away since or foregoing belts altogether.

However, a 10th century grave of a woman in Cumwhitton (Cumbria) has challenged this assumption. One of the female graves contained a belt buckle and strap end, both made of copper alloy (Paterson, Parsons, Newman, Johnson & Howard Davis, 2014). I am fond of the York dyed buckle and since it was not found in a grave context, I feel comfortable including a leather belt as part of a wealthy female impression.

An interesting discussion of belt hardware surviving in female graves can be found in the bibliography. My replica of the belt and buckle was made by Sándor Tar on Facebook.

Leather turnshoes

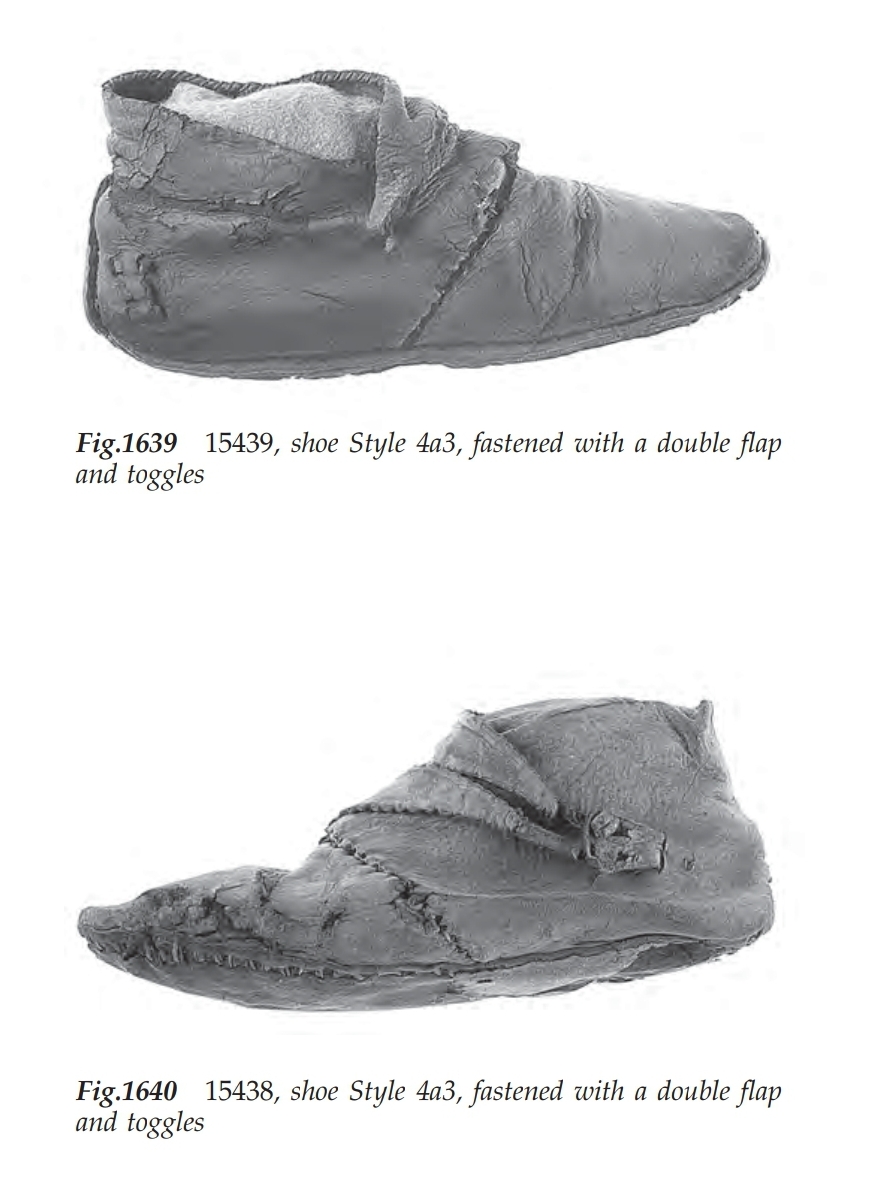

On my feet, I wear leather shoes, based on the Style 4a3. They are of a turnshoe construction and made of vegetable tanned leather. This pair was made by Torvald’s Leather Workshop.

Shoes of Style 4a3 have been found at 16-22 Coppergate from the earliest layers of occupation (mid-late 9th century at the earliest) throughout the whole Anglo-Scandinavian period, but finds of this type are most numerous in the mid 10th century layers (Mould, Carlisle and Cameron, 2003). Shoes of this style were also found at nearby Hungate and fragments indicating this style have been found in Oxford also.

I love this style of shoe, I think they’re really cute and so evocative in their style of Viking Age fashion itself. The only problem? The pair I have have the flaps on the wrong side of the foot! A large group of the shoes found in Jorvík had flaps and toggles over the instep- fastening on the inside of the foot, not the outside. Mould, Carlisle and Cameron (2003) even acknowledge that it seems like toggles on the outside of the foot would be more practical, but I found the opposite to be the case when actually putting them on. I’m aiming to replace these shoes in the future with ones closer to the originals, but they are gorgeous nevertheless and being handmade they are very comfortable.

Underneath these shoes, I wore a pair of woollen naalbound socks, loosely based on the Coppergate socks. However, they have graciously served me for several years now in all weathers and are not fit to be seen. I will certainly cover the mighty Coppergate sock in the future though.

Who might have worn this?

The wife or daughter of a wealthy urban merchant perhaps, someone who had the cash spare to afford dyed garments such as my dress and scarf. Worked amber and jet beads too would likely have been status items, with amber being imported from abroad from the Roman period.

It is also possible that a wealthy woman from more rural areas could wear an outfit like this, the wife of a rich farmer perhaps. This is not the kind of clothing one wears during the working day however, so it would be relegated to Sunday best or feasting clothing (I suspect that this would also be the case for an urban woman.)

References

Ewing, T. (2007) Viking Clothing. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. p9-70.

Mainman, A. J. & Rogers, N. S. H. (2000). Craft, Industry and Everyday Life: Finds from Anglo-Scandinavian York. York: Council for British Archaeology. p2451-2671.

Mould, Q., Carlisle, I. & Cameron, E (2003). Craft, Industry and Everyday Life: Leather and Leatherworking in Anglo-Scandinavian and Medieval York. York: Council for British Archaeology. p3306-3310.

Paterson, C., Parsons, A. J, Newman, R. M, Johnson, N & Howard Davis, C. (2014) Shadows in the Sand: Excavation of a Viking-age cemetery at Cumwhitton, Cumbria. Oxford: Oxford Archaeology North.

Walton, P (1989). Textiles, Cordage and Raw Fibre from 16-22 Coppergate . York: Council for British Archaeology. p285-474

Wincott Heckett, E (2003). Viking Age Headcoverings from Dublin. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy. p9-43.

Bibliography

The entry for the dyed bone buckle from York in the York Museum Trust online collection. https://www.yorkmuseumstrust.org.uk/collections/search/item/?id=7484&search_query=bGltaXQ9MTYmc2VhcmNoX3RleHQ9QnVja2xlJlZWJTVCMCU1RD0mR3MlNUJvcGVyYXRvciU1RD0lM0UlM0QmR3MlNUJ2YWx1ZSU1RD04NjYmR2UlNUJvcGVyYXRvciU1RD0lM0MlM0QmR2UlNUJ2YWx1ZSU1RD0xMDY2JkZOPQ%3D%3D

An article on belt hardware present in female graves in the Viking Age. http://www.medieval-baltic.us/vikbuckle.html

A corpus of 10-11th century images of English clothing in art. http://www.uvm.edu/~hag/rhuddlan/images/index.html

More information about the All Saints Church cross fragment (Weston, North Yorkshire.) https://m.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=26680